Kardingebult (Groningen):

https://maps.app.goo.gl/XuSc9xM9tqucHXjE6

Vuurboetsduin (Friesland):

https://maps.app.goo.gl/Qyhhh4Czq2FCDLg88

00:00 Intro

00:54 Groningen

07:03 Friesland

14:45 Outro

Kardingebult (Groningen):

https://maps.app.goo.gl/XuSc9xM9tqucHXjE6

Vuurboetsduin (Friesland):

https://maps.app.goo.gl/Qyhhh4Czq2FCDLg88

00:00 Intro

00:54 Groningen

07:03 Friesland

14:45 Outro

Adam and Conor interview Jacob Lockwood about his language FIXAPL, an APL with fixed arity (no ambivalence) inspired by APL, BQN and Uiua!

Host: Conor Hoekstra

Panel: Adám Brudzewsky

Guest: Jacob Lockwood

ArrayCast - February 17th, 2026

Try Rocket Money for FREE or unlock more features with premium at: https://RocketMoney.com/bizarrebeasts

Ultra-black generally means a shade of black that reflects 0.5% of light or less. The most cutting edge nanotechnologies are only now starting to unravel how to create these void-like blacks, so how do animals like fish, butterflies, spiders, and birds do it? And why?

Subscribe to the pin club here: https://complexly.store/products/bizarre-beasts-pin-subscription

This month's pin is designed by Víctor Meléndez. You can find out more about him and his work here: https://victormelendez.com/

You can cancel any time by emailing hello@dftba.com

Learn more about the ocean with MBARI here: https://www.youtube.com/@MBARIvideo

Learn more about peacock spiders here: https://www.peacockspider.org/

Follow us on socials:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bizarrebeastsshow/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/BizarreBeastsShow/

Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/bizarrebeastsshow.bsky.social

#BizarreBeasts #ultrablack

-----

Sources:

https://www.mbari.org/news/fresh-from-the-deepmbari-scientists-film-elusive-dreamer-anglerfish-in-4k/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hGOJZsiEAC4

https://news.mit.edu/2019/blackest-black-material-cnt-0913

https://www.nature.com/articles/nmat4633

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ih2_KqBrY8s

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-15033-1.pdf

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(20)30860-5

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/lpor.201300142

https://spie.org/samples/PM229.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780123860224000066

https://www.pantone.com/color-finder/BLACK-C

https://www.colorxs.com/color/pantone-black-c

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2019.0589

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-02088-w.pdf

https://genent.cals.ncsu.edu/insect-identification/order-lepidoptera/family-papilionidae/

https://academic.oup.com/mt/article-abstract/28/6/8/6813774

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005273620301498

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0900155106

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10641-023-01452-8

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/abs/10.1098/rstb.1993.0058

https://academic.oup.com/aesa/article-abstract/78/2/252/2758839

https://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/3920#summary

https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/317065-Cyclothone-acclinidens

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0008622323006346

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0734975014001517

https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/sciadv.1700232

------

Images:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1SkyvIsXI6KMrZ_A4jLtx3WXywVJE2On2EAhy0bJ39ik/edit?tab=t.0

Welcome! Glad you could join us. This is another Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and here’s the plan:

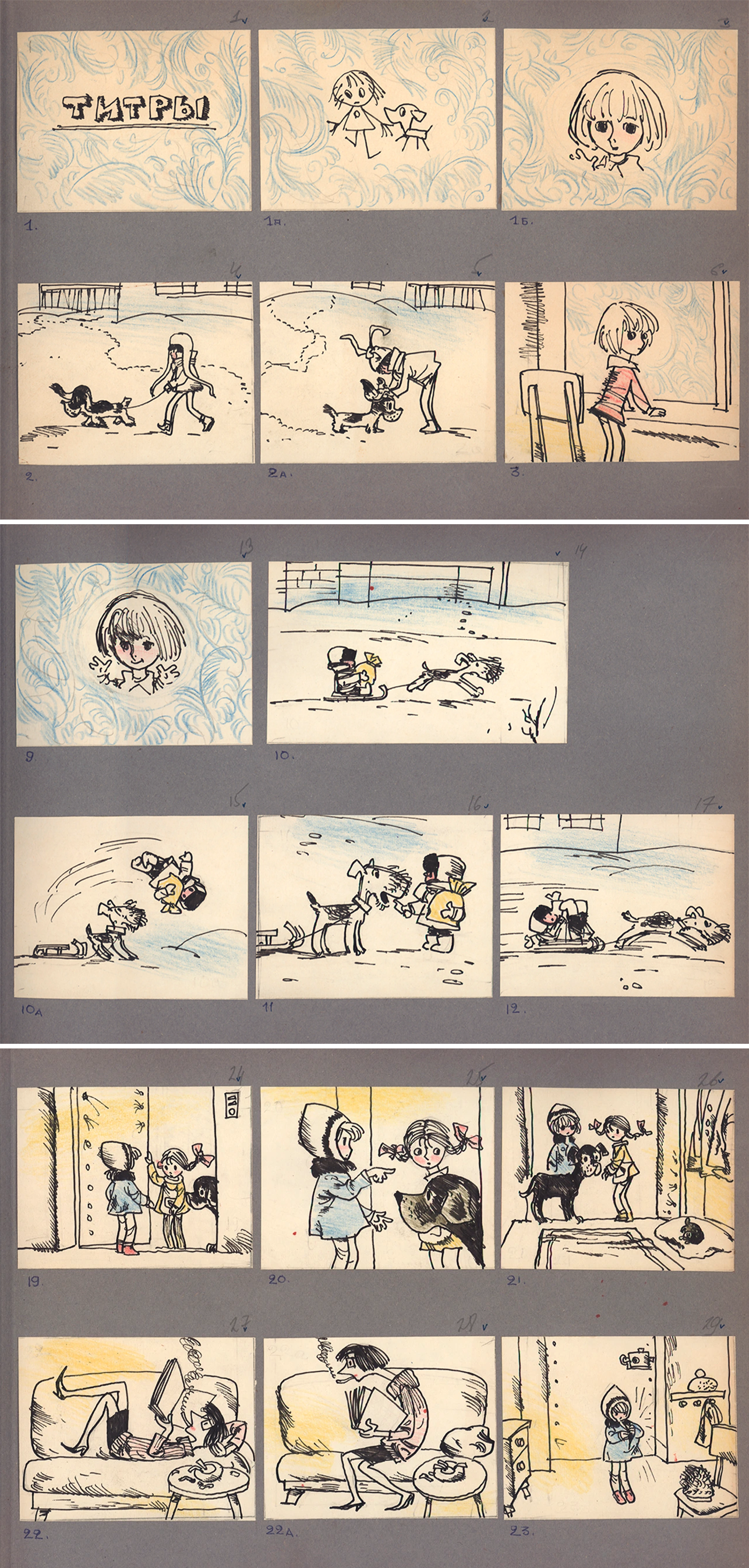

1. Why The Mitten is so special.

2. Animation newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

You can do a lot with a few puppets and a camera — even a phone camera.

By itself, that stuff is enough to shoot a stop-motion film. Adding lights and a set gives you plenty for a full production. The rest is about thinking and execution and soul. Nail those, even on a low-key project, and you might have a gem.

The Mitten (1967) is that kind of piece. It’s a quiet story about a girl who wants a dog — and it doesn’t feel like it aims to be a classic. Even when her red mitten comes to life as a knit puppy, maybe by magic, the film keeps its ambitions small. It’s gentle, and a little funny and a little sad, and then it’s over.

The effect of it sneaks up on you, though. There’s a human warmth here, in everything, that can’t be faked. It became a classic without flash, without pretense. Yuri Norstein (Hedgehog in the Fog) isn’t a huge fan of stop-motion puppets, but he called The Mitten a “deafening discovery” and “a film for all times.”1

Norstein himself animated on The Mitten. It was made behind the Iron Curtain — in the USSR, at the venerable Soyuzmultfilm. A few years later, key members of its team would bring the Cheburashka series to life. But this one stood out in their filmographies even then. The Mitten’s designer, Leonid Shvartsman, remembered an encounter with a colleague once the short was finished:

After the screening of our Mitten, when we were leaving the cinema hall, my childhood friend Lyova Milchin rushed to me and simply kissed me. We both were moved to tears.2

The things that make The Mitten special operate on a subtle level. They’re tiny, but, together, they have power.

Director Roman Kachanov had been working with puppets at Soyuzmultfilm since the late ‘50s. He’d come to realize something in that time. To make an animated character feel alive on the screen, you need unnecessary things. Moving straight from A to B isn’t enough. This is the philosophy he brought to The Mitten — the film for which he saw all his past work as “preparation.”

As Kachanov wrote:

A live actor, a live person, makes a lot of “excess” movements, entirely without thinking about it. You sit down on a chair and instinctively straighten your clothes. You rise from a chair and — without thinking, involuntarily — shake off the crumbs clung to your clothes. You put a dot on a blackboard with chalk and automatically turn the chalk so that the dot gets thicker. But when an animator animates a drawing or a puppet, they forget about this. … And the character becomes like a moving robot that has no incidental or excess movements, nor life-like details, and the viewer subconsciously feels that there is no life in the scene. If a live actor makes these movements involuntarily, then the viewer perceives them just as involuntarily, as unconsciously. …

I call such lively details and touches “planned inconveniences.” They should be in every scene.3

In The Mitten, you sense them in every scene. There’s no naturalistic animation here (nothing moves in an everyday way), but the characters feel fully real thanks to these extra touches. As the girl climbs the stairs to her neighbor’s apartment, one arm is out for balance. When she reaches the top, she’s already starting to tie her hood under her chin. She stretches for the doorbell — and a knee bends up with the effort.

No movement just happens. Every time, it happens in an interesting way.

Late in the story, the girl pets the mitten. Norstein called it the film’s “best scene” and spoke of its “perfection.”4

It went to Maya Buzinova, the primary animator, who worked a lot on the girl and her red puppy. The subtleties that make this scene so tender are very small: a tilt of the head, for example, or the way her hand pulls back and her fingers bend after each stroke. But the emotion of it is undeniable.

Decades later, Buzinova argued that animators hadn’t gotten enough credit for films like this one — for turning “trifling scripts” into believable stories. This was difficult work, especially without computers. As she put it a few years ago:

Compared with my current colleagues, it was very difficult for us ... we did not have a screen to check the previous frame, to monitor. Everything had to be in the head. You had to begin to live the character. You had to begin to be the character. ... In The Mitten, there is just a girl and just a mitten. The key is their connection. The key is to feel that you are performing. To convey love, to convey tenderness. To convey the power of desire: the little girl wants to have a puppy. If there is no love in me for the character, I won’t perform it.

Animation isn’t all, though, that makes The Mitten work. While its script might not have impressed Buzinova, it was an important part of the process. Everything else sprang from it.

The film’s screenwriter was Jeanna Vitenzon. As the story goes, from her apartment window, she’d watched a little girl drag a mitten along the ground by a thread. She put together a draft based on that idea.

Her script landed in the hands of Anatoly Karanovich (The Bath), and he brought it to Kachanov, his protégé. “The idea of The Mitten was liked by Roman Kachanov, an amazing director and person,” said Vitenzon.5 With him, she revised it. They pulled out every line of dialogue: the story would be told in images.

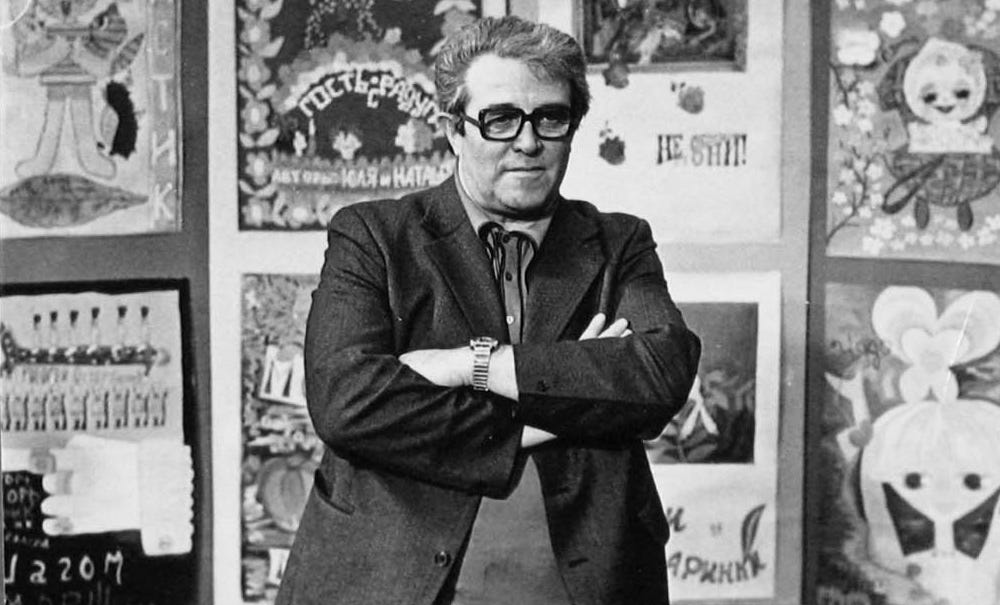

Kachanov was a bulky, muscular man and a boxer. He was also a cinematic poet — Vitenzon recalled that he “could sense such subtle movements of the soul.” Many noticed this about him. “He was strong, tall, athletic. Physically unshakeable,” Norstein said in 2009. “At the same time he had a tender, almost childish soul. It was a charming contrast.”

Like Norstein explained elsewhere, Kachanov was:

… called “the Great Coffer” for his stature and heavy build. The Coffer, still, was endowed with subtlest psychoanalytical wits, great ingeniousness and sound and precise intuition about everything in this life.

Working under Kachanov on The Mitten, Norstein was struck by the director’s “ability to daydream.” Thought after thought came to him about the film, and he would interrupt his animators mid-scene to ask for their feedback.

One of Kachanov’s thoughts was to have Maya Buzinova redo the petting scene, which had already come out well. People were stunned, noted historian Georgy Borodin — and yet the next take was even better.6

Another thought was not to pre-record The Mitten’s jazzy score. Kachanov didn’t want to handcuff himself or his team to a soundtrack. In his view, timing in advance to music stifled both movement and filmmaking. He didn’t mind that the music didn’t line up perfectly.

“At one time, vast importance was attached to synchronicity. It was a time when the modesty and naivety of the story, the absence of characters or psychology in films, were offset by musicality,” Kachanov argued. The Mitten comes from a different place. It’s a story about longing, friendship and loneliness. The feelings happen in a childlike register, but adults can recognize them, too.

To design The Mitten, Kachanov brought in Leonid Shvartsman, who passed away a few years ago at age 101. He was already a legend at Soyuzmultfilm by the ‘60s, having helped to define The Snow Queen (1957) and more. The characters he created for The Mitten were some of his best, and some of his favorites.7

Shvartsman liked to base characters on real people. In The Mitten, the girl’s absent-minded mother was designed after an artist at the studio. He pulled the stern bulldog, who judges the dog show, from Kachanov. “The mighty figure, a serious pensive head without any neck, thick eyebrows, sad clever eyes,” Shvartsman said.

An interviewer once asked Shvartsman if the director had noticed the caricature. “Well, in the first place, everyone else recognized him,” he recalled, “and afterwards, naturally, he did too.”8

Whenever he designed, Shvartsman worked with the animators in mind. His drawings had to function as puppets.9 According to Maya Buzinova, he took pains to create “convenient” characters, ones that stood up well and had proper joints. Paired with his creative spirit, he was a master of his craft. “Each time I saw Liolly [Shvartsman] bending over a scene — the world seemed to me safe and stable,” Norstein said of his time on The Mitten.

With Shvartsman and Kachanov in charge, this was a project in good hands. Add in people like Norstein and Buzinova (“one of the best puppeteers of the Soyuzmultfilm studio,” noted one critic), and a quality film was almost guaranteed.10 But an unusual energy went into the production, too, as Norstein remembered:

… all of us, who took part in its creation, seemed to go a bit crazy. … A masterpiece is never planned, it is always being born by circumstances, even talent is not the main thing here. What is really important — is the point of intersection of deep emotional experiences, vivacity, creative excitement, the birth of a son into the family of Roman Kachanov and his wife’s life on the verge of dying, the feeling of fellowship and the amiable composure of Liolly Shvartsman, tilling the pictorial soil of the film as if it were his cherished vegetable garden — in his steady, unhurried, resourceful manner rich in implicit humor. Such are the bricks a film is made of. It is being filled with the heart feelings of its makers.

Again, the team knew it had done something — as shown by the kissing and crying after the film screened. The Mitten became defining for Soyuzmultfilm. “[D]espite its apparent simplicity, [it] turned out to be a new breakthrough in children’s animation,” wrote historian Sergey Kapkov.11 It won awards internationally.

A couple of years later, Kachanov, Shvartsman and Buzinova would go on to bigger things in Crocodile Gena (1969), the first entry in the Cheburashka series. But The Mitten was the foundation, and some called it Kachanov’s career high even after the success of Cheburashka.12 Here was puppet animation clearly different from the style of Czechs like Jiří Trnka, but not overshadowed by it.

The way Norstein came to move his paper-cutout characters later, in his own films, owes a lot to Kachanov’s approach — and those “planned inconveniences.” Within the tenderness of the movements in Tale of Tales (1979), or Norstein’s Good Night, Little Ones! animation, you can see films like The Mitten.

He didn’t deny it. “I can safely call him my teacher. … It is not a stretch to say that Roman Kachanov created his own school of movement in puppet animation,” Norstein admitted. “I think that without him I would hardly have become a director.”13

This is a revised reprint of an article we first ran behind the paywall on August 22, 2024.

We lost Catherine O’Hara (71). Her voice appeared in many animated projects, including The Wild Robot.

Claire Keane, a key concept artist for Tangled and Frozen, is now on Substack. She’s based in France.

Weilin Zhang is a young star in Japan’s anime industry. Last month, he wrote about his despair with the current business and the value of what it produces. “I sincerely feel that the projects that I am a part of genuinely make the world a worse place,” he admitted.

Readers with Japanese IP addresses can watch the restored films of Tadanari Okamoto, an indie legend, for free on YouTube.

There’s interesting discourse about Russia’s faltering animation field. Writer Dina Goder argued at length that things are grim: artists have left, quality is down, films are “outdated” and heavily censored. The scholar Pavel Shvedov agreed on many counts — but he still has hope, and he pleaded with the youth not to give up.

In Japan, Sunao Katabuchi (In This Corner of the World) has a short film on the way. It’s due online next month.

In other Russian news, a startling proposal would defund film festivals that lack an award category for films about the “SVO,” the euphemism for the war against Ukraine. (Also, director Alexander Sokurov and the influential Yuliana Slashcheva were removed from a major film council.)

In Britain, Little Amélie, Zootopia 2 and Arco are among the animated nominees at the BAFTAs. See the full list.

This coming week, the Animation First festival opens in America. Its retrospective on the films of Raoul Servais is a highlight this time.

A few years back, Anton Dyakov got an Oscar nomination for BoxBallet (2020). Now based in France, he’s working with a Norwegian studio to produce the film Black Box, revealed this week. See details here and the trailer here.

On that note: we wrote about BoxBallet and Dyakov’s interrupted career.

Until next time!

From the section on Roman Kachanov in Animation: A World History (Vol. 2) and Norstein’s preface to A Classic, Liolly by Name, in the Land of Animation (Классик по имени Лёля в стране Мультипликации). We’ve cited both throughout.

Shvartsman said this in Leonid Shvartsman: Master of the Image (Леонид Шварцман. Мастер образа.), another major source.

From Kachanov’s essay in The Wisdom of Fiction (1983), the source for his quotes today.

The point about perfection comes from Roman Kachanov: Cheburashka’s Best Friend (2011).

From Borodin’s blog.

Shvartsman placed the cast of The Mitten among his favorite characters in this interview.

From Kommersant.

The quote about Buzinova comes from The World of Animation by Sergei Asenin.

See the Encyclopedia of Domestic Animation.

Ivan Ivanov-Vano called The Mitten “undoubtedly the pinnacle” for Kachanov in his book Frame by Frame (1980).

See Cinema Art.

Welcome! Thanks for checking in. It’s another Sunday issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and this is the slate:

1. Animating in the early days of the personal computer.

2. Newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

There was a question in the days when video games were young.

People figured out how to move graphics on a screen — see Pong from the early ‘70s, for example. This alone was a feat. Fast forward a decade, and the growth was visible. You had Donkey Kong beating his chest in the arcades; personal computers like the Apple II were running games where helicopters flew around with energy and bounce.

Games and animation went together — that much was clear. Like animated films, these things often (if not always) brought artwork to life. How deep was the link, though? How many techniques from the animation world could really, effectively cross over?1

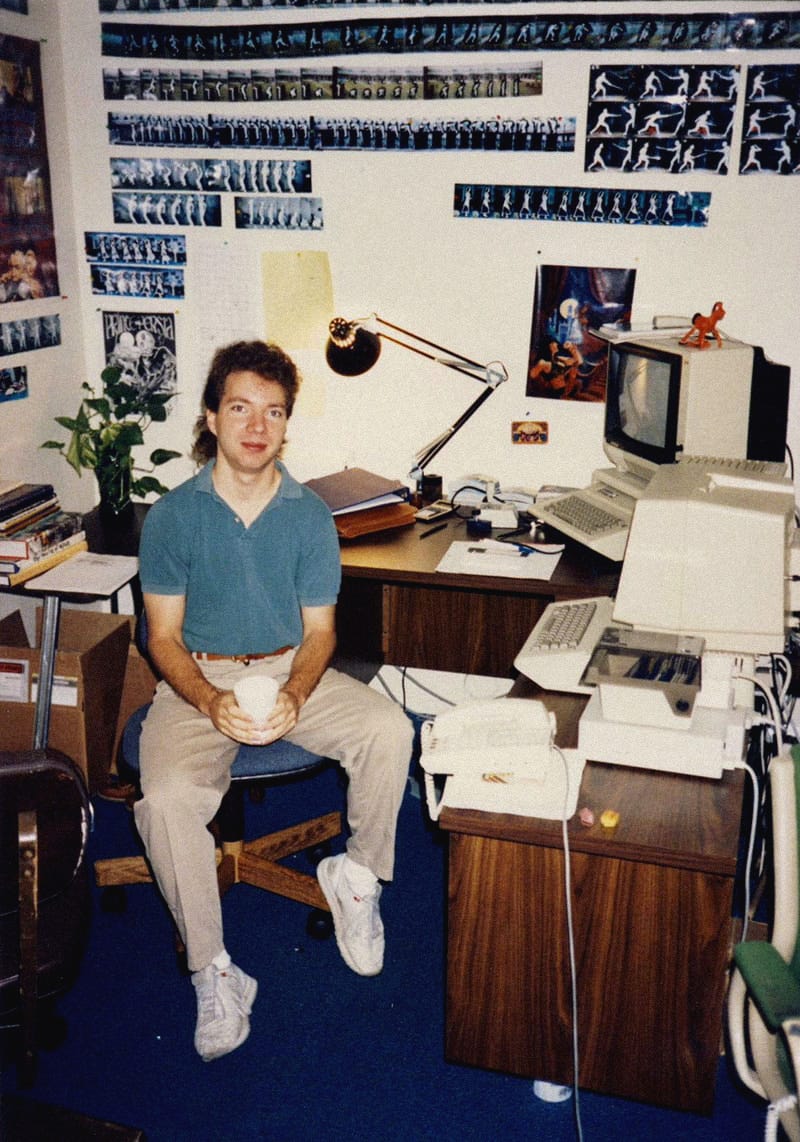

A twenty-something coder from New York explored that question during the ‘80s. His name: Jordan Mechner. He self-described, among other things, as an “amateur animator.”

Mechner got his first Apple II as a teenager and fell in love. “I wanted to produce animations,” he said. “I knew from making those animations that the computer was powerful, and that it was capable as a games machine.”2

After years of writing games, Mechner released the one that made him a star: Prince of Persia (1989). It drew from the “great old Hollywood swashbuckling movies,” he said — like those starring Douglas Fairbanks. And animation was at the center. “Prince of Persia is the culmination of a lifelong fascination with animation,” noted the game’s manual.3

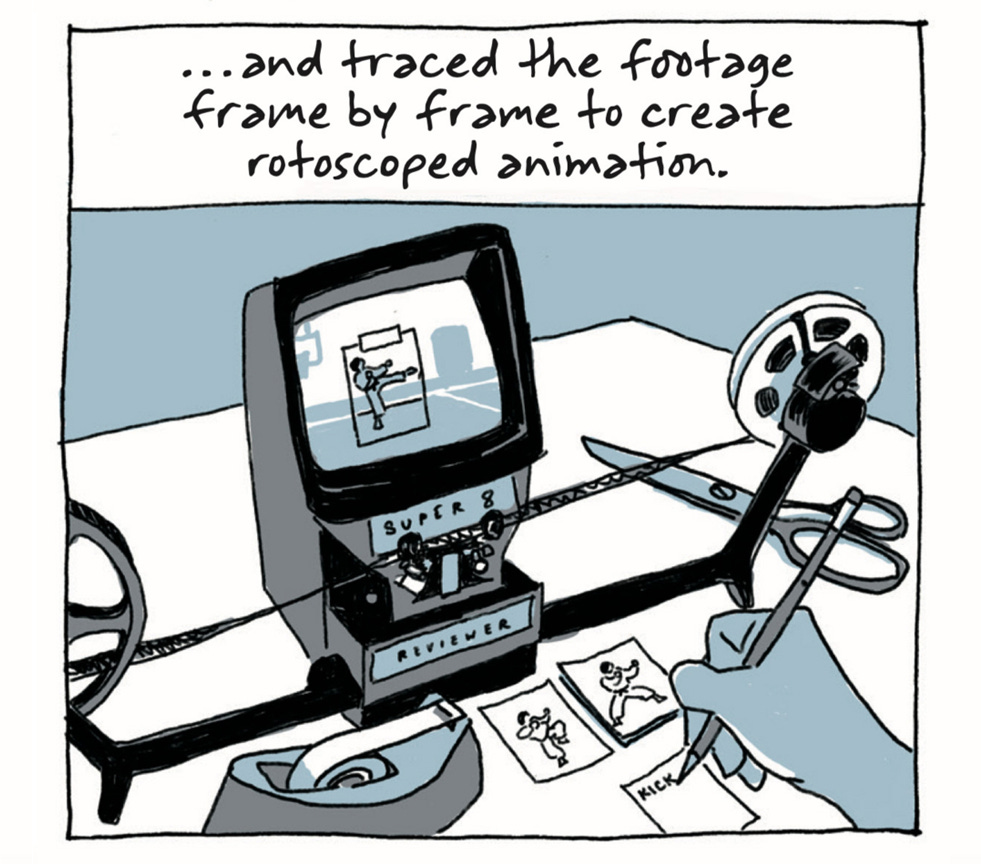

Famously, Mechner’s project rested on an experiment in digital rotoscoping.

Prince of Persia comes from an era when high-end PCs did way, way less than today’s low-end smartphones. And the game wasn’t made for the best computers of its time. Mechner’s target system, the Apple II, was already a fossil by 1989.

“[T]he Apple II’s memory was 48K,” Mechner said a few years back. “That’s less than a normal text email.”4

The original Prince of Persia displays big, blocky shapes in a handful of colors. Early in development, Mechner noted that the action was planned to run at just 15 frames per second, much slower than a movie. But he knew visuals were about more than tech. How they moved came down to animation technique — and it meant everything. He wrote in his journal:

The figure will be tiny and messy and look like crap… but I have faith that, when the frames are run in sequence at 15 fps, it’ll create an illusion of life that’s more amazing than anything that’s ever been seen on an Apple II screen. The little guy will be … this shimmering little beacon of life in the static Apple-graphics Persian world I’ll build for him. 5

Mechner felt it would work because he’d done it before. He knew how to get believable movement into the Apple II’s tiny memory.

It was what he’d achieved in his game Karateka (1984), whose lead character punched, kicked, walked and ran in a compelling way via rotoscoping. “What made the big difference was using a Super 8 camera to film my karate teacher going through the moves, and tracing them frame by frame on a Moviola,” Mechner said about that project.6

The trick originated in animated films — an aid for the movement of the humans in projects like Snow White (1937). Disney’s animators traced footage of live actors and deviated: they tweaked shapes, removed frames, kept the best poses. Mechner didn’t know that yet, but he did know that his own hand-drawn animation was “stiff,” and not the “realistic simulation of karate fighting” he wanted.7

His father was the one who suggested video footage (he even wore a gi and helped Mechner shoot a few movements). The only problem was digitization. These were the days, Mechner said, when the “challenge was getting [the footage] into the computer, which, of course, is something we can do now by pressing a button on a cellphone.”8

Mechner’s setup for Karateka was wild. Over his Moviola screen, he taped thin paper, upon which he traced key frames from the Super 8 footage beneath. Then he took his pencil sketches to a VersaWriter — an early drawing tablet — and traced them on that. Frames of movement became pixels on his computer monitor. From there, he cleaned them up with an art program he’d coded.9

His animation changed when he started taking from life in this way. The little details he’d missed became obvious. Mechner said:

I remember the frame of the high kick, the fighter leans back and also the arm goes back. … [I]n the beginning, when I tried to do a frame of a high kick, you know, it was more idealized. I didn’t realize that the body would have to move quite that far back.

Mechner recorded his impression of the initial tests in his journal. As he wrote, “When I saw that sketchy little figure walk across the screen, looking just like [my karate teacher] Dennis, all I could say was, ‘ALL RIGHT!’ ”

Karateka was unusual for the time, and it sold well — over 400,000 copies, in fact. The whole thing was a product of Mechner’s ambitious thinking about games. “I was taking film studies classes (always dangerous) and starting to get delusions of grandeur that computer games were in the infancy of a new art form,” he said, “like cartoon animation in the ‘20s or film in the 1900s.”

Those ideas influenced him again when he undertook Prince of Persia, not long after Karateka. He felt that games “had a lot of the same limitations that silent film had,” and he wanted to borrow the solutions of the silent era. Mechner aimed for a game in which “personality is expressed through action.”10

To do it, he returned to digital rotoscoping.

His younger brother David — a rising talent at Go, the board game — helped this time. “He was 16 years old [and] in high school ... He wasn’t the greatest athlete, but he was willing to do it for free,” said the elder Mechner.

In ‘85, they went to the parking lot of Reader’s Digest, near his brother’s school, to get footage with a VHS camera. It was an expensive toy then — “I couldn’t afford to own it,” Mechner admitted. (Guiltily, he refunded it after the shoot.) As he said later:

I made him do all of the moves that I thought would be needed in the game: running, jumping, climbing up on the generator that was sitting in the middle of the parking lot.11

Once again, the problem was converting the movement into animation. Mechner’s method was even wilder this time.

For his Apple II, he bought a “digitizer.” It was a special card that connected to a CCTV camera.12 “[It] let you basically point a little black-and-white video camera at an art stand, and it would digitize it and put it back on the computer [as pixels],” Mechner said.

Early tests were not promising. The images weren’t resizable, and the VHS footage wasn’t in the stark black and white that the card registered well. What he’d shot was “useless” as-was. Mechner needed a workaround: a way to make the movements readable by the card.

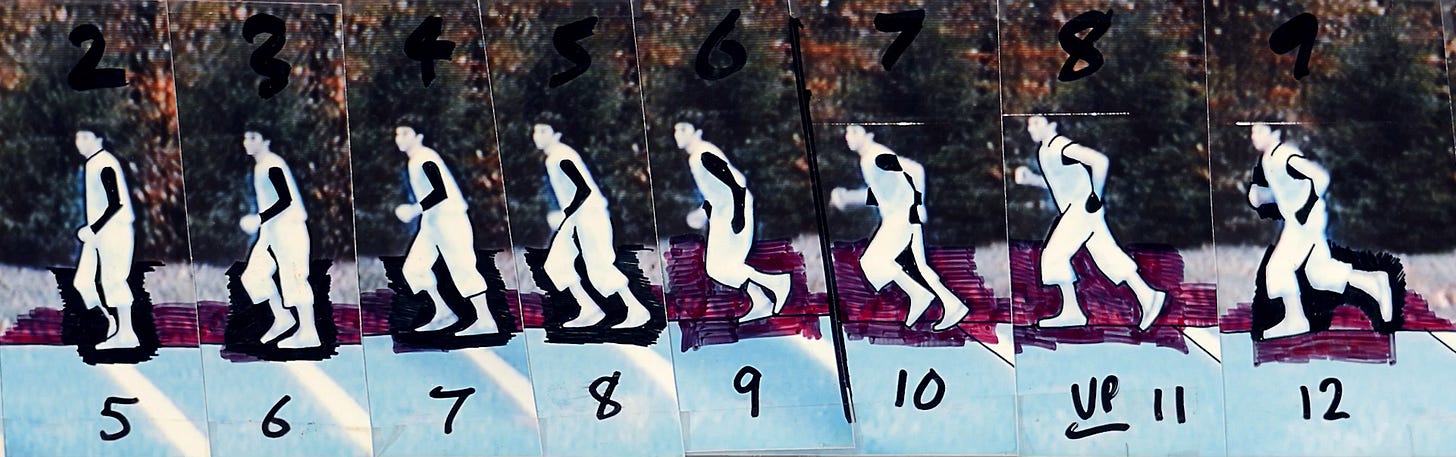

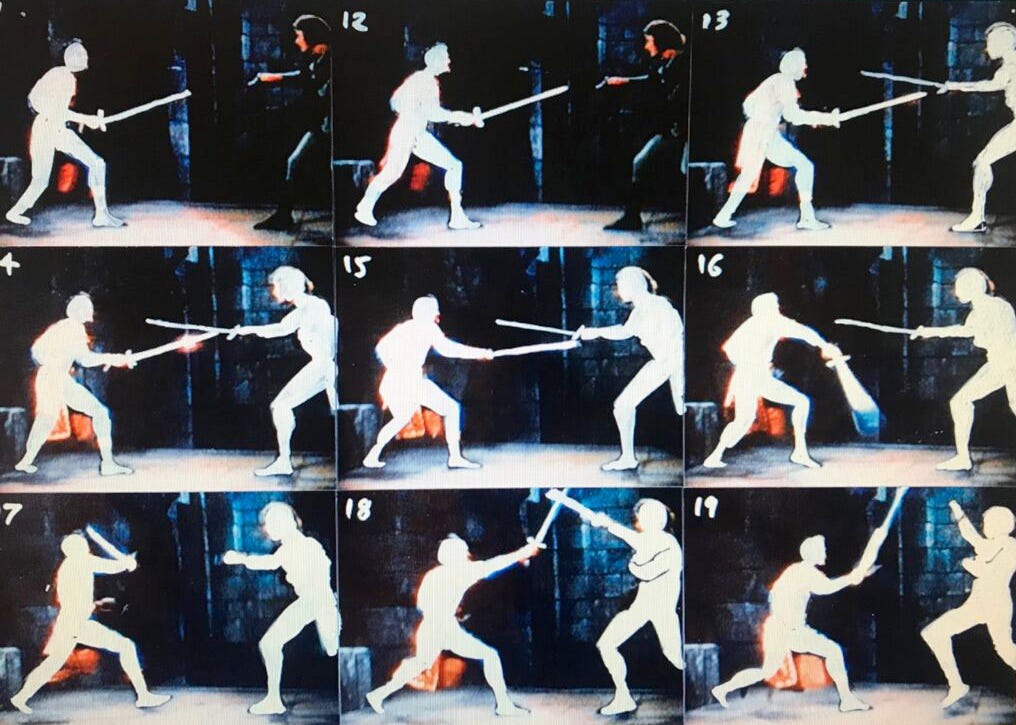

So, he hooked up a screen to a VCR, and set a Nikon camera (35 mm) on a tripod in front of it. “[Y]ou basically drew all the curtains in the room and then popped the videotape in the VCR, hit play, hit pause, did a frame advance,” he said. Mechner photographed “every third frame,” reducing his brother’s movement from 24 frames per second down to eight.

The photos were developed and then processed further. “I highlighted these shots with a black marker to produce a series of silhouettes,” Mechner explained. Specifically, he used a Magic Marker and Wite-Out to define the lines of each frame of his brother’s movement as clearly as possible. The next step was to put them through “a Xerox machine to get a really clean silhouette.”

The result: more than a dozen sheets of paper, all covered with black-and-white animation frames in sequence. Those went in front of the CCTV camera to be digitized, one at a time. This whole agonizing process had taken “months,” he said.13

“I love the quality of the just-digitized roughs,” Mechner wrote in his journal toward the end of ‘86, after seeing the tests. The final step was to “clean it up and stylize the figures” — and to “enhance” certain motions, like the long jump, to be larger than life.

Mechner built the rest of Prince of Persia around the lead character’s movement. As he put it, “My basic concept was to create the most lifelike, fluidly animated human game character ever ... trying to survive like Buster Keaton in a world that was dangerous.”

Throughout production, he kept including more rotoscoped motions, which brought extra difficulties. For one thing, there was the hardware — new frames ate up space in the Apple II’s memory. Another thing was his brother’s growth spurt between the first video shoot and the second (“with the magic of my cartoonization process, I was able to correct for this,” Mechner said).

But combat was the big one. Sword fights got added to Prince of Persia in late 1988 — and they needed a bunch of new animation. As Mechner studied the fights in early swashbucklers like Captain Blood for reference, he started to feel just how exciting his project was. “This is going to be the greatest game of all time,” he wrote to himself in December of ‘88.

Ultimately, The Adventures of Robin Hood solved the combat. Going over the film’s climactic fight, Mechner found “six seconds” that matched his needs. As he said:

… the camera angle has them [fighting] in exact profile. This was a godsend. I did my VHS/one-hour-photo rotoscope procedure, spread two-dozen snapshots out on the floor of the office and spent days poring over them trying to figure out what exactly was going on in that duel, how to conceptualize it into a repeatable pattern.

What he got was simple, thrilling back-and-forth action. It captured the thing he wanted: the old Hollywood style in which “the blades clash high and low in a kind of balletic rhythm.”14

Again, Prince of Persia was released for an ancient piece of hardware. By the time the game came out, in September 1989, the Apple II was dying off. Mechner’s project didn’t really sell — maybe 500 units per month at first.

Those who encountered his animation were wowed, though. “You really have to see it to believe it,” noted one newsletter. The game’s packaging hyped up the animated characters in terms that, according to another publication, would “be the height of marketing arrogance if [they] weren’t, quite simply, true.”15

Prince of Persia became one of those long-tail games. It ended up on a ton of platforms, ported by a ton of different teams. Versions reached Japan, Europe. Years later, Mechner met people who’d played it in the USSR: “I was amazed and moved to realize that my game had such a cultural impact, even behind the Iron Curtain, which was an unknown world to me as an American at that time.”16

Over time, it sold millions of copies. The versions people played weren’t quite Mechner’s original — the game’s visuals were redone many times for newer, stronger hardware. The Apple II’s harsh, limited colors went away. Yet Mechner’s animation, the basis of the project, stayed in place. And it stayed strong.

Which was the thing: making the animation believable and exciting wasn’t really about tech. Despite all the tricks Mechner used for it, this was an artistic problem. The arrival of newer hardware, more colors, faster frame rates and higher resolutions didn’t outmode the simple, lively motion in Prince of Persia — how could they? The great animation of the 1920s, a century ago, still looks great now. Movement doesn’t age so easily.

Back in 2020, Mechner published his journals from the Prince of Persia era as a book. On the cover is his game’s hero — rendered in two colors and in razor-sharp, Apple II-style pixels. We find the character mid-leap, in a pose that Mechner got and refined from his brother 40 years ago. It’s still full of energy.

In America, Adobe announced plans this week to kill off Animate — and then backtracked after an outcry, thankfully.

The Palestinian animator Rama Heib is among the first artists to win a grant from the Palestine Film Fund (for the short Issa and the Forest).

An American music video, Spirit Jumper, aims to digitally recreate the look of classic ‘80s and ‘90s cel animation. It does an impressive job — especially in the use of light. Director Josh Fagin writes that he went for “that ‘dangerous’ light, the kind that actually feels like it’s burning the screen,” as seen in Akira.

In Hungary, the Kecskemét animation studio has a new leader for the first time since 1971. László Toth (an animator on The Secret of Kells and The Red Turtle) took over from Ferenc Mikulás.

On that note, in America, Bob Iger will step down as the head of Disney in March. His replacement is Josh D’Amaro from the company’s parks division.

A little late, but worth noting: David was produced in South Africa, and its box office of $83 million represents a “breakthrough” for animation from the continent.

In Germany, new rules require “streaming platforms and TV broadcasters … to invest 8% of their [German] revenue” into projects produced in the country.

There’s an effort in America to build a National Animation Museum, and CalArts signed on last month.

The Japanese animator Kazuya Kanehisa was featured by Cartoon Brew in a piece with lots of fascinating insights about his work, based on “Showa-era” cartoons and aesthetics.

In Britain, the Cardiff Animation Festival revealed its program for 2026. It opens in April.

Last of all: we looked at three projects from China’s Flash scene — and at how that scene built the current Chinese animation boom.

Until next time!

Don Bluth was among the first major animators to get involved in games, and to test whether ideas from the animation world really fit them. His Dragon’s Lair (1983) was a hit that saved his company. But it always had a problem — he admitted that testers told him, “[T]here ain’t no game there.” (See the April 1984 issue of Computer Games.)

Bluth’s team tried to make Dragon’s Lair more interactive after that feedback. Even so, it remained more film than game.

Most of these initial details about Mechner come from The Comics Journal, Retro Gamer #77 and the Videogames Hardware Handbook (Vol. 2).

See Mechner’s bio in the original User’s Guide and, for the quote about swashbuckling, Engadget.

From Ars Technica’s video interview with Mechner.

From The Making of Prince of Persia, Mechner’s published journals. One of our main sources today.

Mechner said this in an interview for Game Design: Theory and Practice (2nd Edition). We used this a couple of times.

The line about stiff animation comes from The Making of Karateka, a wonderful piece of history, used a lot today. Mechner’s comment about realism was made in The One (January 1991), another key source.

That was Mechner talking about Prince of Persia at his 2011 GDC talk, the source of many quotes and details in this issue.

Some of these details appear in The Making of Karateka: Journals 1982–1985.

The second quote appears in an archived Edge article, used several times.

The device in question was seemingly Computech’s Diplomat Video Digitizer from the mid-1980s. See this flyer about the card for technical details.

Mechner’s point about “months” comes from a recent article by The Guardian.

From Mechner’s interview in Retro Gamer #165.

These quotes come from Computer Entertainer (October 1989) and Computer Gaming World (December 1989), both reviewing the Apple II version.

Quote from Mechner’s interview in Retro Gamer #118.