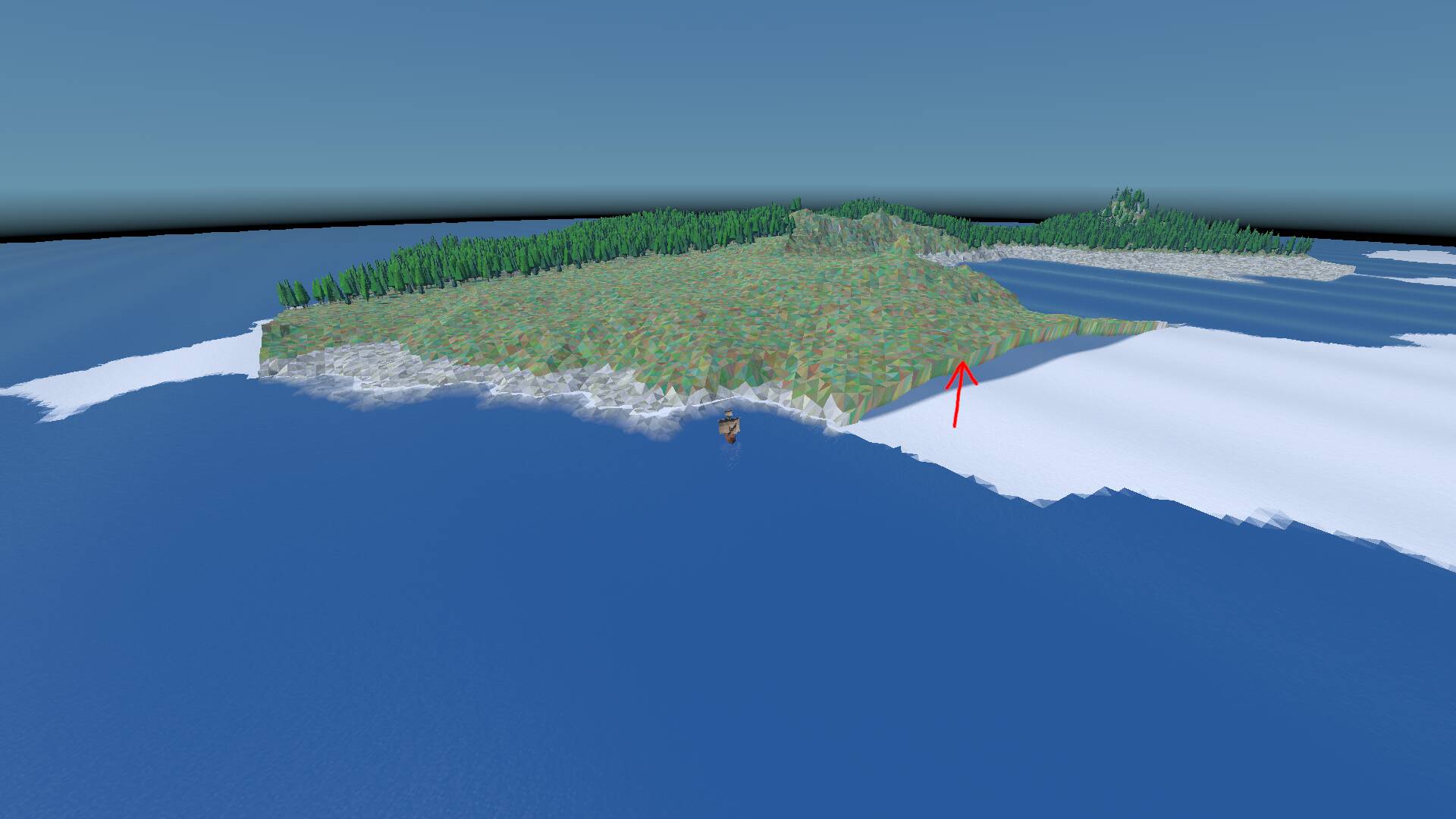

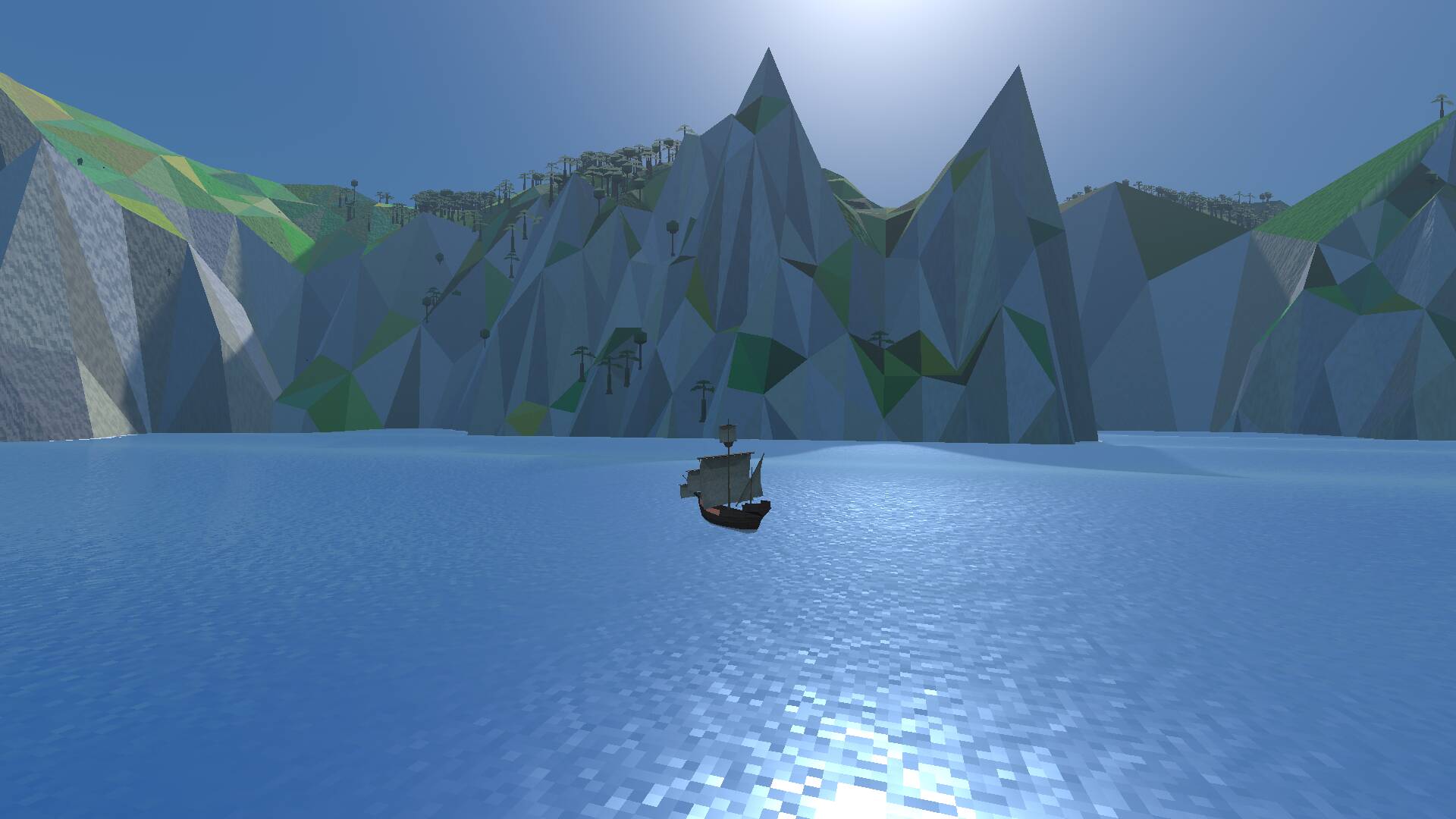

Even though the in-game world is fairly small compared to Earth, I want it to feel big. Part of that is being able to see things that are far away.

For context: by now, I have settled on a third-person “chase camera” rather than a top-down view. It feels so much more immersive, and makes the gameplay (in particular, matching up maps to your surroundings) more interesting as well.

Remember that my world is now a flat plane that wraps around, rather than an actual sphere. However, it would be great if we could still make it look like a sphere, so that distant lands would gradually appear over the horizon. Mountains would be visible from a greater distance, so that the terrain actually matters beyond just the shape of the coastline.

Until now, I’ve been using a view distance of 5 km. That’s still a lot compared to other open-world games! But a landmass at 5 km does not look very far away, because it’s so big. For gameplay purposes, it would be good if view distance could be increased to about 25 km. Otherwise, the part of the world that the player can see is too small compared to the maps, and they won’t have anything to orient themselves by.

How does it work out if we just look at the geometry? My planar planet is 512 km wide, so let’s pretent that’s the circumference of a spherical planet. Its radius would then be 83 km. Terrain generation is scaled down relative to the real world, so that the tallest mountain is about 2500 m high. Assuming a ship of up to 25 m tall, the mountain’s peak will be visible over the horizon from 22 km away. That’s pretty close to the 25 km I figured out above, so I decided to sail with these numbers for now: let’s fake a planet radius of 83 km.

We now have some problems to solve.

World wrapping

To actually be able to sail around the world, you need to be able to sail off the west edge and reappear at the east edge, and vice versa. That’s easy enough to implement with some modular arithmetic applied to the ship’s coordinates. However, any nearby objects and terrain must also exhibit the same wrapping: if you are near the west edge of the world, you should be able to see across it, so anything near the east edge would have to be moved near you as well. This, too, can be implemented with some modular arithmetic.

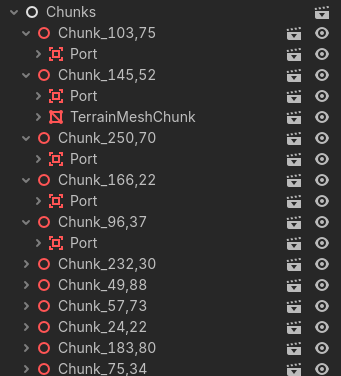

However, it would have to be applied to every object in the game individually. That’s tedious at best, and bad for performance at worst, so I came up with the solution of parenting every object to a 2×2 km chunk. Only the chunks are moving around; their children just come along for the ride. The node hierarchy looks like this:

Here’s an example of how a nearby NPC ship would become visible, even though it’s all the way on the other side of the map in world coordinates:

The chunks themselves take care to move their children to adjacent chunks whenever they cross a chunk boundary, so the code of individual objects doesn’t need to care about the chunking at all.

Floating origin

As before with the spherical world, we’re going to run into floating-point precision issues. Godot by default uses 32-bit floats for object and vertex positions, which have only 23 bits of precision; at 512 km from the origin, the distance between two successive floating-point numbers is about 6 cm. The official recommendation in the Godot docs is not to go beyond 8 km for a 3D third-person game, and not beyond 64 km for any 3D game.

I started out hoping that this wouldn’t be an issue, but it turns out to be real: far away from the world origin, the ship started jittering weirdly, and the sails started jittering relative to the ship. A solution was needed.

Building Godot with 64-bits precision is possible, but adds a lot of overhead: now every vector and matrix in the game uses twice the memory, including the large procedurally generated terrain meshes. Would that be a problem? Not necessarily, but it turns out there’s now an easier solution.

Since we’re moving chunks around anyway, we can implement a floating origin system there as well. Just before rendering a frame, the chunk containing the player’s ship is moved to the global origin (0, 0), and all other chunks are positioned relative to it:

This ensures that every object we care about remains close to the global origin, where floating-point precision is sufficient. As long as none of the code assumes that global coordinates (relative to Godot’s global origin) are the same as world coordinates (relative to the north-west corner of the world map), this works great: the jitter is gone.

Planet curvature

Let’s take a look at how we could implement a fake planet curvature. In particular, I want distant objects to gradually sink below the horizon.

This could be done in a vertex shader: simply compute the distance to the camera (measured on the horizontal plane), calculate how far downwards the vertex should move, and move it:

The drawback is that this shader would need to be applied to every object in the world, meaning I would have to use custom shaders everywhere and couldn’t benefit from Godot’s built-in materials anymore. Tedious! Another drawback is that the visible meshes would no longer align with their physics shapes, which becomes relevant if we want to do object picking (e.g. clicking on the peak of a distant mountain to set a course towards it).

But I had an idea I wanted to try. Now that we have chunks, maybe we could pull the chunks themselves downwards, and have all their children come along for the ride?

My first attempt was to introduce some skew. In 3D games, the position and orientation of an object is usually represented as a matrix, and mine is no different. Godot uses 3×4 matrices: a 3×3 part to represent rotation and scale, and a 3x1 part for translation. But rotation has 3 degrees of freedom, and scale has another 3, so that means that we have 3 more degrees of freedom we can play with to make the chunk align (somewhat) with the sphere. Because chunks are in the y = 0 plane and are neither rotated nor scaled, the matrix looks like this, where tx, 0, tz is the translation vector (the chunk’s position):

1 0 0 tx

0 1 0 0

0 0 1 tz

If we want to move points within the chunk only on the vertical axis (y), depending on their position in the xz plane, we have two components rx, rz we can play with, as well as ty:

1 0 0 tx

rx 1 rz ty

0 0 1 tz

My idea is then as follows: modify these variables rx, rz, ty in such a way that the chunk’s corners end up on the sphere. Because we have 4 corners and only 3 variables, this is impossible; instead, we do it only for the 3 corners that are closest to the camera, and let the 4th end up where it will. It’s hard to draw in 3D, but in 2D you can see the idea better:

Every object inside these chunks will end up skewed as well, but because the effect is slight, this shouldn’t be visible.

Here’s how it looks when I modify the curvature in real time:

At lower curvatures, it’s quite effective!

However, there’s a problem with this approach that might not be obvious at first: physics. The built-in Godot Physics engine is well known to be bad at anything except pure translation and rotation; it doesn’t even support scaling. The newly integrated Jolt engine is better in this regard, but it draws the line at skewing, and starts emitting a lot of errors if a physics shape like a cylinder has any skew introduced to it.

So, let’s try something so stupid that it couldn’t possibly work: do not skew chunks at all, but just move them on the vertical axis, like this:

Amazingly, at small curvatures such as I’m using, this works just fine and the visual difference compared to skewing is not even noticeable. You might think it would introduce visible cracks between terrain chunks, but no: because farther chunks are moved farther downwards, the cracks are always hidden behind nearby terrain. It’s a keeper!

Terrain LODs

Now that we have the ability to make stuff gradually appear over the horizon, we need some stuff that actually will gradually appear over the horizon. With a ship of 25 m tall, even though the horizon itself is (surprisingly) only 2 km away, we can see tall mountains at a distance of 25 km. So a draw distance of 5 km is not nearly enough anymore.

It’s easy enough to increase this value in the configuration, but this increased the amount of terrain by a factor of 5² = 25, and tanked the frame rate. Some quick math shows that, at the terrain resolution of 8 m that I’m using, the 50×50 km patch of terrain around the player consists of 39 million triangles, and this is too much for my GPU.

Fortunately, we don’t need that many triangles, because on distant terrain they’re smaller than a pixel. It’s time to introduce a LOD (level-of-detail) scheme to our terrain: render nearby terrain at full detail, but reduce the number of triangles on terrain chunks farther away.

A classic problem with this are seams, or cracks, between adjacent terrain meshes of a different LOD. It’s often just a few pixels, but it’s still quite visible especially in motion. Here, I tweaked some values to make the problem more visible:

There are various solutions. The most elegant is to introduce special bits of mesh to cover the cracks, which are only made visible when the two adjacent terrain chunks are currently displayed at different LODs. Due to all the different edge cases (pun wholeheartedly intended), it’s surprisingly fiddly to get this right.

Fortunately there’s a simpler method, which is to simply add a ‘skirt’ of quads that hangs down from the edge of each chunk:

The normals on the skirt are copied from the adjacent vertices, so they receive the same lighting, and it won’t look as if there’s an actual small cliff there. And with that, the crack is gone:

This should also cover up any cracks caused by moving chunks vertically, though I haven’t spotted any so far.

Impostors

The trees I added in the previous post make a huge difference to the believability and sense of scale of the terrain. It would be sad if they couldn’t be rendered up to a large distance.

However, as it currently stands, being near a rainforest will drop the framerate to about 40 fps; the tree meshes take 15 ms to render. Since I want this game to run well on potato hardware, it should run at around 150-200 fps on my mid-range Radeon RX 7600 card, meaning a frame budget of only 5-7 ms.

The standard trick is to not render full meshes at a large distance, but rather pre-render the mesh into a texture from various points of view, and then just render a single quad with the texture applied: an impostor.

Godot doesn’t have support for impostors built in, but adding tooling inside the editor is really easy, so I built this quick and dirty impostor baking scene:

It iterates through all the tree meshes at 8 different angles, and renders each to a suitably sized viewport through an orthogonal camera (to simulate an infinite distance). Each orientation is rendered twice: once to capture colour and alpha, once to capture normals. The textures have pretty low resolution, but that’s fine, because they’re never viewed up close anyway:

These are then applied directly to the impostor quad, depending on the viewing angle:

This increased the frame rate from 40 fps to about 130 fps. There’s some more low-hanging fruit that will improve the frame rate further, so this is fast enough for the time being.

All together now

Let’s see all of the above in action while the player sails towards a remote island: the distant terrain, planet curvature, and tree impostors. I’ve edited the video for brevity, because it ran over 3 minutes; one of the biggest game design challenges will be to make sure the player has something to do during these long voyages.

The transition from impostors to real geometry is still fairly noticeable, probably because the impostors cast a smaller shadow. But it’s plenty good enough for now.