Welcome! This is another Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s our plan today:

1. Nobody, and what’s happening without the Oscars.

2. Animation newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

1. The underdogs

Next Sunday, the Oscars happen. The nominees have been public for a while. And, in the list of animated features, there are conspicuous holes.

Major and highly regarded projects got nominated, no doubt. Among them: the biggest box-office smash in Hollywood animation history (Zootopia 2), and the most-watched original film from Netflix (KPop Demon Hunters). The two contenders from Europe, Arco and Little Amélie, have won awards worldwide.

If you follow animation closely, though, you might wonder: “what about China?”

Although Zootopia 2 broke records, Nezha 2 broke more of them. It out-earned every movie everywhere during 2025 — and it’s widely loved. Yet it isn’t present here. Reports suggest it wasn’t even submitted to the Oscars.1

There’s a second Chinese absentee, too. It’s a wonderful film watched by too few outside China. In its home country, it was a “dark horse” phenomenon last year — almost $250 million in revenue, on a budget below $10 million. People fell in love with it.2

It’s called Nobody, and its stateside distribution has been pretty thin. You can find subtitled copies floating around unofficially on YouTube — if you know where to look. It’s our favorite mainstream movie we’ve seen from 2025, and it belongs on any list of last year’s best animation.3 But it won’t be competing next Sunday.

Like with Nezha 2, there are reasons for Nobody’s omission. It didn’t make the longlist, possibly because its brief release in American theaters wasn’t tuned to get it qualified.4 This isn’t simply an oversight by the Academy.

Yet it still makes this year’s Oscars feel a bit provincial. The largest animated feature of 2025 won’t be there, nor will (arguably) the finest. And it’s a shame — because Nobody, especially, feels like a sign of animation’s future.

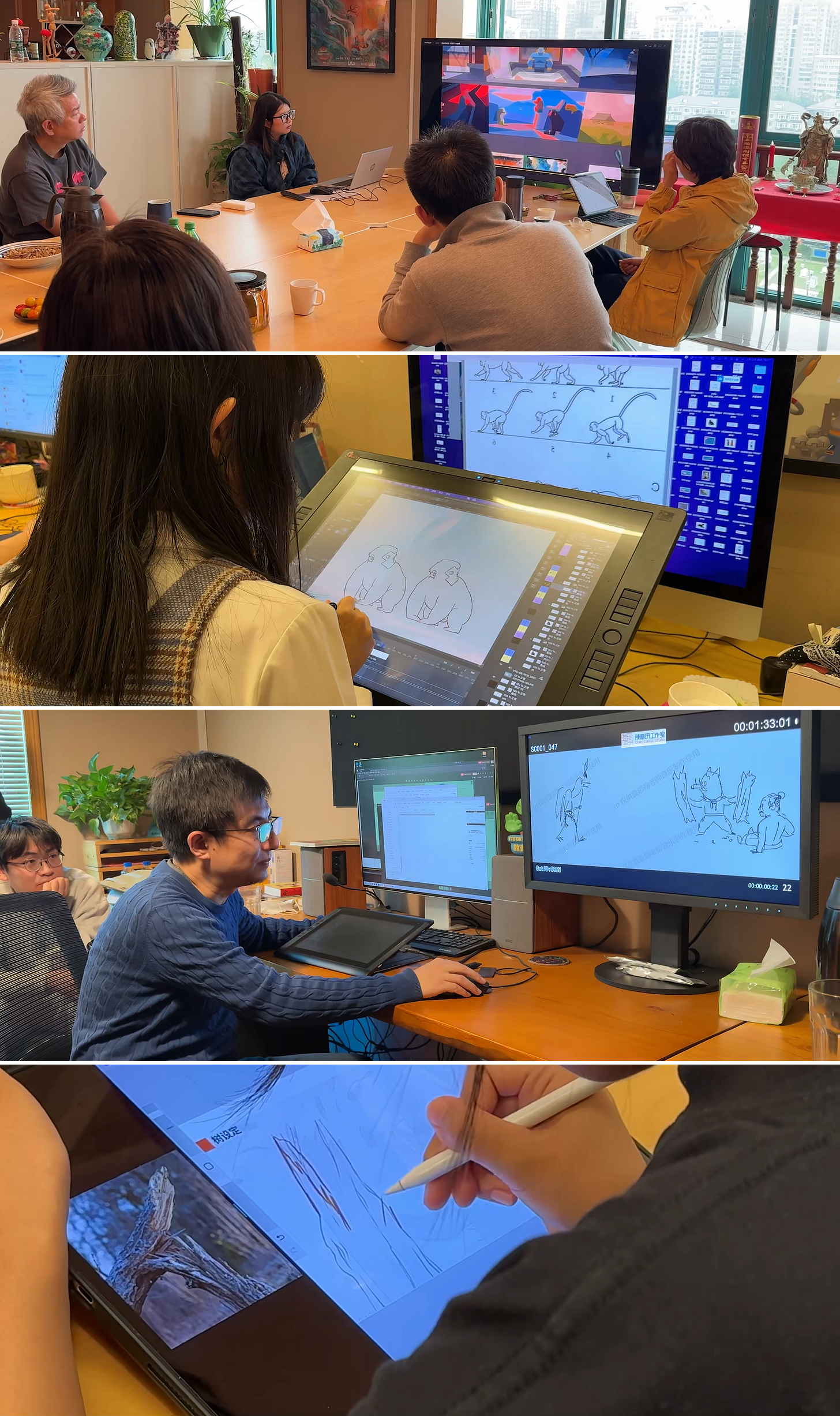

Before Nobody, Yu Shui wasn’t exactly a nobody himself. Years ago, his student film About Life (2004) won prizes, and his Flash series FOF and His Story (2013) had its fans. But, because the industry was weak in China, animation stayed an indie side project for him. As he said, “At the beginning, I had nothing and worked alone.” His day job was teaching at a university in Beijing.5

Yu was no star as a director. Slowly and gradually, though, he gathered allies — and opportunities arrived. “After more than 20 years in the industry,” noted an outlet in 2025, “Yu Shui finally got his chance.”

For those who haven’t seen Nobody, it’s about frauds. A ragtag band in ancient China sets out to become immortal. All involved are animal-monster outcasts: former bandits, henchmen, con artists. On their quest, they impersonate a few heroes they’ve heard about — namely, the Monkey King’s group. Since they don’t know what Sun Wukong or his friends look like, they hire a concept artist to spitball, and they choose the lineup that feels right.

It’s very funny. There are smart, layered jokes throughout the script. In fact, even the drawings and movement are funny — often subtly, in ways not usually seen.

Then, over time, the emotions sneak up.

In China, Nobody was known to get theaters crying. The frauds — a boar, toad, weasel and gorilla — grow as they try to live up to their pretend roles. What begins as farce turns into halting, absurd, small-scale but real heroism. No knowledge of Journey to the West is required to grasp the arc. It’s universal.

Yu and his team aimed at a broad audience — even an international one. As they said, this is a film about the “nobodies” whose tales aren’t told. “Most of the world consists of ‘nobodies.’ That’s why their stories resonate so powerfully,” Yu argued. Pointedly, his film’s stars don’t appear in the text of Journey to the West.

Yu places himself in this invisible group. Like he put it:

Most people, myself included, are just ordinary individuals. But how do ordinary people establish themselves and navigate life? So many things are beyond our control — whether it’s the demands of our career, family or society. Essentially, numerous external forces collectively shape our lives. The core message of our film is that: can you truly understand yourself and find your own path?6

When Yu’s break came, he was already in his 40s.

Shanghai Animation Film Studio, the most senior company in Chinese animation, released an anthology of shorts back in 2023. First up was a creation of Yu’s — a piece called Nobody (watch). It was an indie film in spirit, but made at industry scale. Surprisingly, it blew up. Yu’s work was suddenly mainstream.

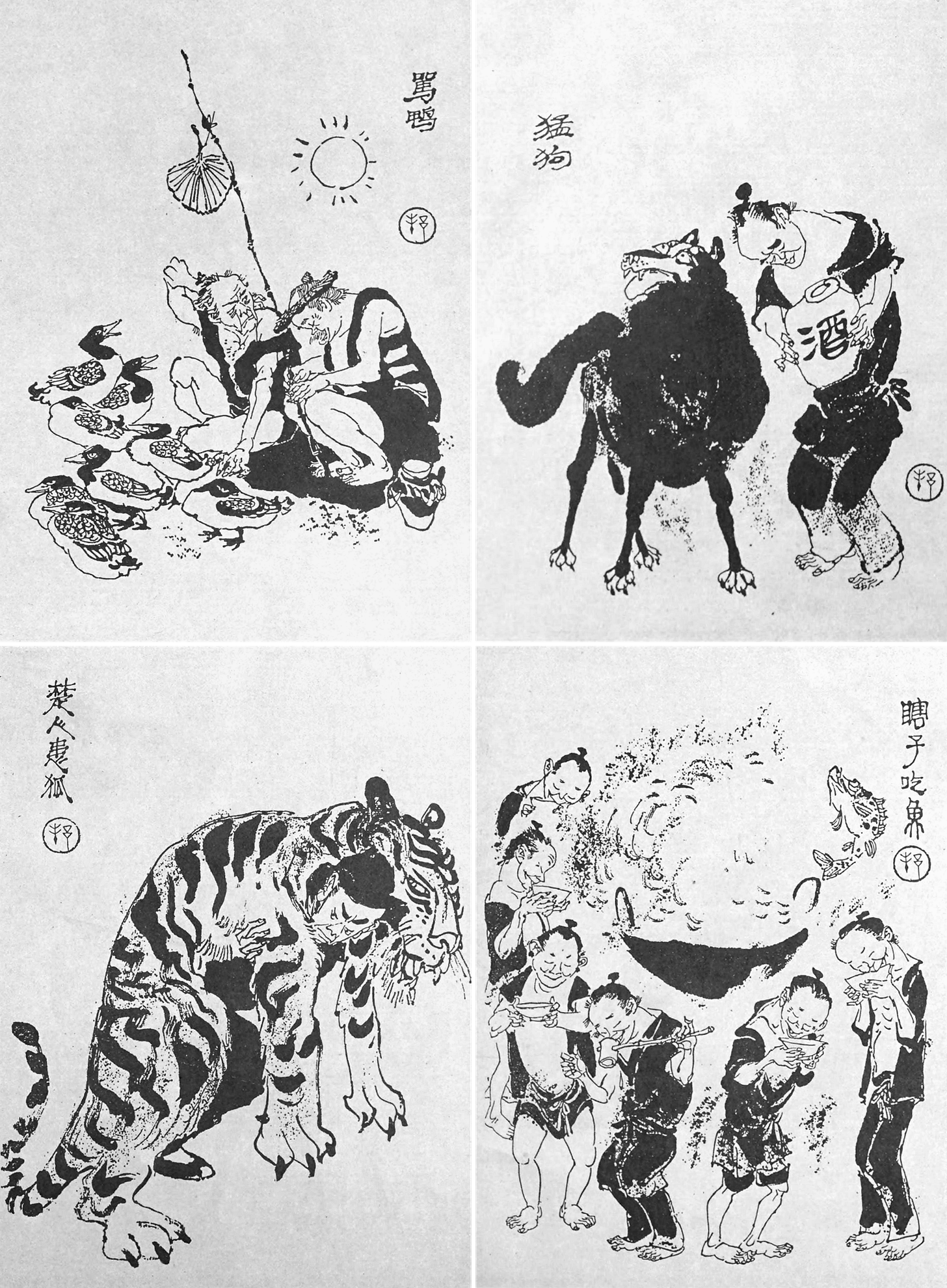

The short is likewise about a boar-creature who wants to become more than a lackey. And, visually, the whole thing is tied to Chinese tradition: ink-wash painting and local styles of cartooning come together on screen. The result was excellent, and people higher up thought it was ripe for a feature-length treatment.

That was the plan even before the anthology was done. When the producers saw Yu’s script in 2021, they asked him to develop it into a feature, side by side with the creation of the short. The art director of the long version, Chen Liaoyu, called it “neither a prequel nor a sequel to the short ... we’ve developed a completely new, parallel story.” They’re different takes on the same subject matter and characters.7

The Nobody feature built on the aesthetics of the short, too. Once again, it’s steeped in Chinese tradition. Like Yu said:

For this film, I did a lot of field research in Shanxi Province, my hometown, and discovered so many treasures. For example, places like the Guanyin Hall in Changzhi, the Chongqing Temple and Faxing Temple in Zhangzi County … I found the craftsmanship of these Buddhist statues [in Shanxi] to be deeply moving. The reason I incorporated these elements into the film is that they’re grounded — they come from real life, from the world around us. ... With this foundation in reality, I felt much more confident in my creative process.8

China’s local visual arts played a large part, too. For the backgrounds, the team studied ink-wash painting and mimicked the techniques of the masters. For the cartoony characters, they looked to the ink drawings in 20th-century lianhuanhua comics — from artists like Dai Dunbang.9

Yu’s guiding concept for Nobody was “mythological realism,” or a down-to-earth take on Chinese myths. It affected everything — from the asymmetrical character designs to the way those designs move.

“We’re portraying the most ordinary people from everyday life,” explained Chen Liaoyu. “If the little pig monster came out like Mickey Mouse, with elastic, smoothly flowing deformation and stretching, it would just be an American pig monster. But we want precisely the opposite: first, it needs a feeling of lived-in texture, a little bent and clumsy.”10

That said, Yu and the team aren’t isolationists. China was opening up to foreign animation when Yu was young — he saw stuff like Toy Story and Japan’s Lunlun, The Flower Angel, and it stayed with him. Nobody pulls ideas from beyond the local as well.

For one, the team wanted a sense of “believable” and “cinematic” space, as if the characters exist in a solid and three-dimensional world. That isn’t typical for ink-wash painting, where Western ideas of “light and shadow and perspective” are minimized. But Yu’s group combined the two approaches. The art couldn’t be too flat or too photographic; it was a balance.

As Chen Liaoyu explained:

… we had to figure out how to integrate the effects of light and shadow within ink-wash painting. … Traditionally, Chinese painting doesn’t emphasize the portrayal of light and shadow as much. However, as a film, it’s inherently an art of light and shadow. ... Beyond just the ink brushwork, we needed to add lighting, space and even texture. This approach allows the audience to appreciate the beauty of Chinese aesthetics while experiencing the intuitive realism of cinema.

The thought and theory behind Nobody feel like classic Shanghai Animation stuff. In the studio’s heyday, films like Three Monks (1980) came about like this — research, refinement, analytical hairsplitting. Every facet was intentional.

It’s why those projects turned out so well, and so rich. You feel a similar richness in Nobody. In fact, some of the surviving Shanghai Animation veterans were consultants, and they hadn’t lost their “keen eyes,” Chen said. Their feedback helped.

And the success of Nobody proves the old ideas still work. Today, China produces much of the world’s most lavish, over-the-top animation — just look at Deep Sea (2023). Many of those movies are worthwhile. Yet almost none of them were as popular as Nobody, a low-budget 2D film with little in the way of flash.

As Chen said, the mentality was: “it’s not that you can’t be cool, but don’t be cool for the sake of being cool, or show off for the sake of showing off; above all, you need to tell a good story.” The camera doesn’t fly around much, and even the animation in the fight scenes stays clear and direct. But Nobody gets the quieter, more difficult parts really right, and that was enough to grab people.

It shows what’s possible in China’s rising animation industry. It also shows that tiny movies, wherever they’re made, continue to have a shot against giant ones. Nobody is only one instance. After all, Flow made €50 million and won the Oscar last year with even fewer resources.

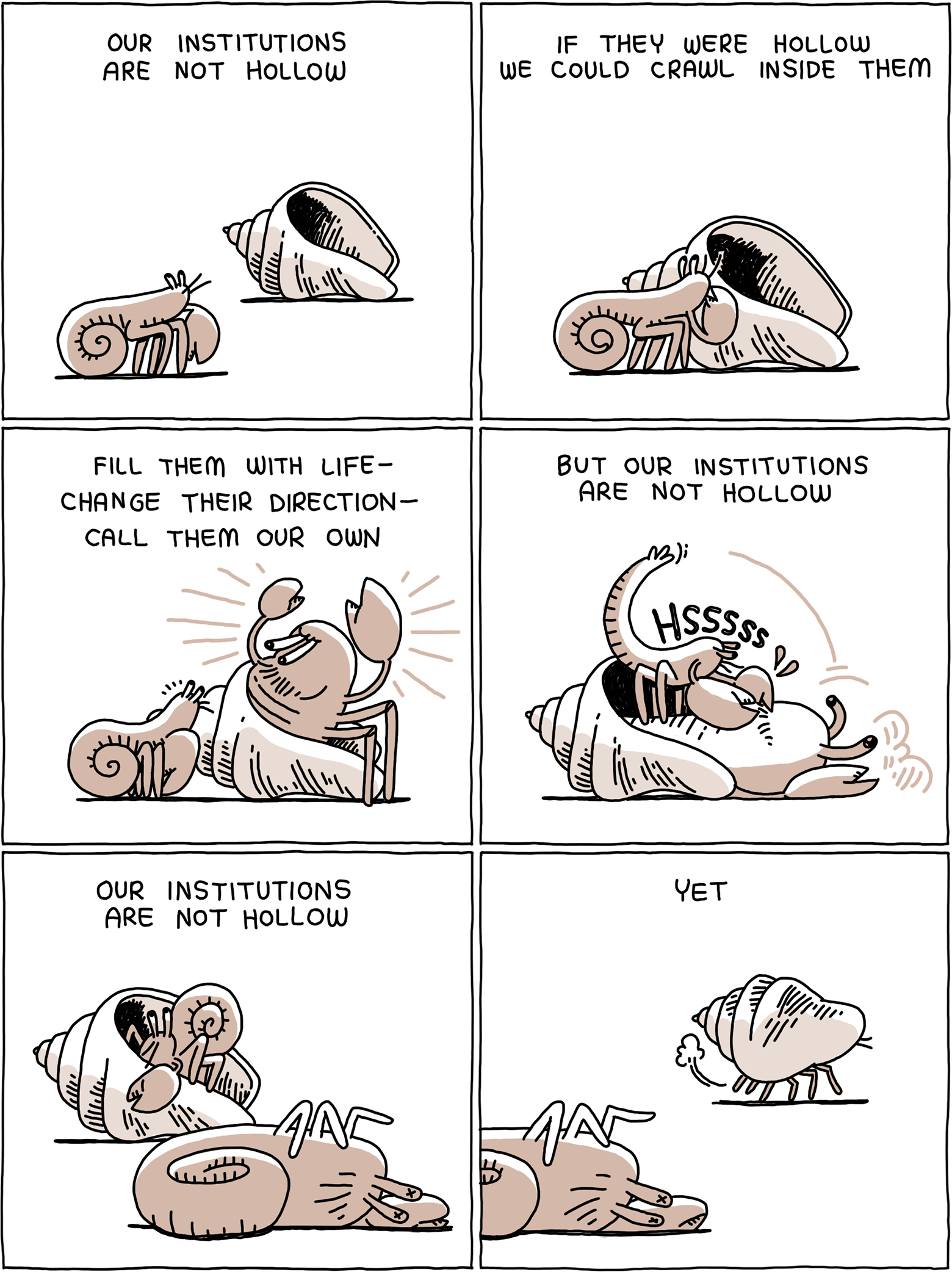

Nobody won’t have the chance to repeat that performance next Sunday. With or without the Oscars, though, the rise of small, thoughtful and risky animation is happening.11 There’s an audience for it. The untold stories are coming to light.

2. Newsbits

Ireland’s Cartoon Saloon released the teaser for Kindred Spirits, the latest from director Tomm Moore. Hype for the project was significant at the recent Cartoon Movie event.

On that note, check out the teaser for Kigali Night that screened at Cartoon Movie in France. We saw the film pitched at Annecy last year — keep an eye on this one.

One more teaser trailer: Only Rats, a stop-motion short from Spain.

As the American blockade against Cuba worsens, the animation workshops of Animaluz Academy are continuing — even during power outages. See posts on the group’s Facebook page (here and here).

In America, animator Coleen Baik became a MacDowell fellow. She continues to offer one-of-a-kind insights into the animation process over at The Line Between.

That recent Gorillaz video came from The Line in Britain. Writing for Cartoon Brew, Kambole Campbell uncovered the technical processes that gave the animation its retro look.

Kyra Kupetsky, creator of the American series Chikn Nuggit, reportedly left her project in protest of enforced GenAI use.

In China, a new season of Yao: Chinese Folktales (the origin of Nobody) debuted earlier this year. Anim-Babblers explored one of the entries, animated with wool.

A few months ago, the Russian film Father’s Letters popped up online for free. It’s a tribute to the victims of Stalinism.

Today, in America, Los Angeles Filmforum held a screening called Femme Grotesquerie, featuring work by Sofia Carrillo, Victoria Vincent and more.

The government of Russia declared it illegal to advertise on Telegram, as part of its growing campaign against the platform.

Last of all: a gorgeous resource on the art and animation of an Italian great.

Until next time!

Discussed by Gold Derby.

See the South China Morning Post, Maoyan, this article, Elle China, Forbes China, Poison Eye and Wuhu Animator Space. Some of these were used multiple times.

To date, Jonni Peppers’ hyper-underground feature Take Off the Blindfold Adjust Your Eyes Look in the Mirror See the Face of Your Mother remains our favorite of 2025.

For these details and more information, see the Harvard Film Archive, AWN, Jiupai News, Sohu Digital World, ArtLinkArt, Douban, Southern Weekly, China Daily, Variety China and ScienceNet. A few were key sources throughout.

See China Newsweek and the foregoing sources.

From the Global Times.

See People’s Daily (here and here), Jiefang Daily, Red Star News and this article. Most were valuable today.

See Xinmin Weekly, used several times.

Notably, some of the Oscar nominees this year fall into that very category.