This week, I want to keep unloading my Tolkien-related thoughts, turning from last week’s character study to a look at the way ‘magic’ and spiritual power work in Tolkien’s legendarium and in particular to how contests between fundamentally magical beings in Middle-earth are decided. This is a topic that I think even the best adaptations have generally failed to grasp, representing (as Peter Jackson does) contests between supernatural beings as involving fireballs and telekinetic shoves. Rings of Power likewise seems, in its depiction of Gandalf, committed to magic that is very open, flashy and kinetic (and sometimes wielded by beings who ought not have it, reflective of a misunderstanding of where supernatural power comes from in Middle-earth).

So I want to lay out my reading of how all of this functions. While Tolkien’s magic system is often described as a ‘soft’ system (or even not a system at all), as if it had few rules or boundaries, I would argue that in fact we can perceive the basic patterns for how Tolkien understands supernatural power to exert itself in his legendarium and how supernatural being compete in strength.

Once again I should note we are not entirely departing from the craft of the historian here. After all, we frequently read the writings of past societies looking to understand how they viewed the world and part of that is often understanding how they understood the metaphysical (that is, supernatural) nature of their world: how do they imagine things like curses and gods and magic work? We’re effectively performing the same analysis, but on Tolkien’s writings, with the aim of trying to suss out how he imagines ‘magic’ works in his constructed ‘secondary‘ world.

Our starting point is something Treebeard says to the Gandalf as the Fellowship passed Orthanc on their way home, at the end of the story: “You have proved mightiest, and all your labours have gone well.” (RotK, 287). It is a striking statement and it picks up something Gandalf said at the Council of Elrond, “There are many powers in the world, for good or for evil. Some are greater than I am. Against some I have not yet been measured. But my time is coming” (FotR, 266). Treebeard is observing that the measuring has now been taken and Gandalf has “proved mightiest.” But measured against whom?

At first, one might think that Treebeard is merely commenting on Gandalf’s clear superiority in strength over Saruman, but this won’t do: Gandalf spoke to Treebeard after breaking Saruman’s staff in The Two Towers (TT, 226), so Gandalf’s victory there is no new information for Treebeard to observe with this statement. And in any case, that would merely make Gandalf mightier. Nor will it do to simply dismiss Treebeard as speaking empty words: for his slow pace, he is ancient and has seen many ages of the world and many powers as one of the oldest beings in Middle-earth53 and what is more, no one corrects him in that moment, despite quite a few of ‘the wise’ being present.

No, I would argue that what Treebeard is saying is that Gandalf has, at the end of his many labours, been measured against and “proved” mightier not merely than Saruman or the Witch King but mightier than Sauron and thus the “mightiest” creature in Middle-earth.54 And no one corrects him – because there is nothing to correct. It is a revealing reading! Although Gandalf and Sauron never met face-to-face, never appear to contest directly, it imagines Gandalf to have been, in a very real sense, in contest with each other not only in the physical (‘Seen’) world, but also in the spiritual (‘Unseen’) world, which is, as we’ll see, the more important one.

But how can Gandalf have proved mightier than Sauron, a being he never meets in person?

But first, as always, if you want to help support this project you can do so on Patreon! And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on Twitter (@BretDevereaux) and Bluesky (@bretdevereaux.bsky.social) and (less frequently) Mastodon (@bretdevereaux@historians.social) for updates when posts go live and my general musings; I have largely shifted over to Bluesky (I maintain some de minimis presence on Twitter), given that it has become a much better place for historical discussion than Twitter.

Magic in Middle-earth

Before we dive in, I think we need to distinguish here between three different kinds of power in Tolkien’s writings that we might call ‘magic,’ though in each case, Tolkien himself might object. I am going to term them as craft-magic, spiritual power and then a subset of spiritual power, dark magic. We can begin with craft-magic: Elves and Dwarves sometimes produce objects or effects which are marvelous out of their deep knowledge and connection to parts of Arda. Bread that is wondrously nourishing, doors that open on their own at a word, swords that glow blue in the presence of orcs and so on. These are not magic per se – they do not really involve a supernatural power – but rather understood in Tolkien as something more like technology: wondrous, magical-seeming results borne of the tremendous skill and deep knowledge of the crafters. We are setting this sort of ‘craft-magic’ aside for now, except to note that it is unlike the other two forms of ‘magic’ we’re looking at, as it is not spiritual or supernatural at all.

By contrast, the Ainur – that is, the greater Valar and lesser Maiar (of which Sauron and the wizards are examples) – have access to what I am going to term spiritual power, because they are angelic, supernatural beings. Having been involved in the Song of Eru and the very creation of Arda, these beings are able to a degree to reshape Arda around themselves. This is the sort of ‘magic’ – spiritual power – that we’ll be focused on here. Like all ‘magic’ in Tolkien, such power is an expression of the primacy of the Unseen over the Seen and in a sense as a result such spiritual power does not effect or perform but rather reveals: the true, Unseen nature of the world is revealed by the exertion of a supernatural being and that revelation reshapes physical reality (the Seen) which is necessarily less real and less fundamental than the Unseen.

As an aside, note those moments where Gandalf’s manner suddenly changes and a character glimpses, however briefly, his true being as an angelic Maia of tremendous power. It is not that Gandalf makes himself seem bigger or older or wiser (nor is it that Saruman makes himself seem like a coiled snake, ready to strike, TT, 219), but rather that in those moments characters who normally can only observe the Seen world momentarily glimpse the deeper truth of the Unseen world.

Denethor looked indeed much more like a great wizard than Gandalf did, more kingly, beautiful, and powerful; and older. Yet by a sense other than sight, Pippin perceived that Gandalf had the greater power and the deeper wisdom, and a majesty that was veiled. And he was older, far older. (RotK, 30, emphasis mine)

This spiritual power also has a subset, which we might term ‘dark magic:’ certain non-Ainur are able to wield magic that is not craft-magic and is seemingly invariably evil. The Mouth of Sauron “learned great sorcery,” for instance (RotK 182), and the Witch King can make his sword ignite and command Barrow-wights. Such ‘dark magic’ is actually spiritual power, one step removed: what these mortal magic users command is actually the disseminated remains of Morgoth’s spiritual power, diffused through Middle-earth.55 What these evil magic users have learned, in essence, is how to manipulate elements of this ‘Morgoth-stuff’ to produce magical-seeming effects; because the ‘stuff’ is of Morgoth, the effects and their users are generally evil.

As an aside, I think the power of the Rings introduces some complexity into this question. The One Ring is very clearly an extension and focusing of Sauron’s own spiritual power and perhaps to some degree also his knowledge of ‘dark magic,’ and the fact that the Seven and the Nine, in which Sauron had a hand, tend to lead their holders to bad ends suggests to me they too had some element of either Sauron’s or Morgoth’s power in them. But it is unclear to me if the Three rings are similarly tainted: on the one hand, they are free of Sauron’s influence in the absence of the One Ring, but on the other hand, they fail when the One Ring is unmade, suggesting that some essential part of their design drew on the same source as it did, which is fundamentally Sauron’s spiritual power. Yet they do not seem to corrupt their wearers on their own, which might suggest they are close – or at least closer – to pure ‘craft-magic.’ My own suspicion is that in their design, drawn from the Seven and the Nine, there is some part of Sauron’s spiritual power reflected in them (included unintentionally by Celebrimbor), but that they are mostly ‘craft-magic,’ but I do not think this reading is at all required by the text.56 As an aside, it is striking that in the Lord of the Rings, the one instance we see that we might read as an elf doing magic rather than just craft-magic – Elrond flooding the Ford, comes from Elrond, bearer of Vilya and thus may have been an extension of his ring’s power.57

In any case, we’re interested here in spiritual power, the sort of magic Ainur like Gandalf, Sauron, Durin’s Bane and Saruman can wield – and which some of Sauron’s lieutenants can wield either as a delegated power from Sauron or as an extension of ‘dark magic’s’ manipulation of ‘Morgoth-stuff.’

While Tolkien is sometimes slotted into ‘soft’ magic systems or even no system at all, I want to argue here that spiritual power follows a clear pattern in Tolkien. What makes it tricky to assess as a ‘magic system’ is instead that spiritual power works at a very profound level, making it easy to mistake the most important uses of it as ‘chance’ or ‘happenstance’ when in fact we are observing the surface emanations of something much deeper. But in most cases – arguably all of the, – this spiritual power does follow a system, if we are attentive enough to detect it. Naturally, the fellow we see work the most of this sort of ‘magic’ is Gandalf and so upon Gandalf we shall focus, as he confronts and defeats other spiritually powerful beings.

Obvious Magic

We want to start by grounding our understanding in moments that are obviously expressions of spiritual, supernatural power: the obvious magic. That will help us set the ‘ground rules’ by which we assess some of the less obvious instances.

I can think of a few core examples of this sort of ‘obvious magic’ that we see first-hand in the text.58 Gandalf twice conjures fire (FotR, 347, 357) with an invocation, although this is an interesting example as it is the only time Gandalf uses another language (Sindarin) to do so, rather than doing so in the ‘plain’ (English standing in for Westron) language of the text; as we’ll see, I have my suspicions as to why. Gandalf’s confrontation with the Balrog is likewise a clear instance of supernatural power, a confrontation between to Maiar in which Gandalf breaks the Bridge of Khazad-dûm (FotR, 392). He also describes opposing Durin’s Bane – though he doesn’t know it yet – with a “shutting spell” that is answered by a “counter-spell” which he answers by a “word of Command” (FotR, 388) though we get this described to us rather than see it. The other very clear example is Gandalf’s breaking of Saruman’s staff (TT, 222). If we put these events together, we might begin to understand how Tolkien expresses spiritual power and in so doing begin to detect more subtle instances of its expression.

The first thing to note is that in every case there is a clear verbal invocation. Speaking seems to be, if not required, a normal part of expressing supernatural power, particularly larger expressions of such power (more than, for instance, a flash of light). But the form of that invocation too is interesting. Whereas ‘magic words’ are common in a lot of fantasy fiction, only one ‘spell’ is spoken not in ‘plain language:’ the conjuring of fire. On Caradhras, Gandalf ignites wet wood under heavy wind with something called a ‘word of command’ – a phrase Gandalf uses again later – in Sindarin, naur an edraith ammen, literally, “fire for saving us” (FotR, 347). Later, against the wolves, Gandalf uses a longer, more specific version of the same ‘spell:’ “Naur an edraith ammen! Naur dan i ngaurhoth!” which we might render, “Fire for saving us! Fire against the wolf-host!” (FotR, 357). This is, to my recollection, the only time Gandalf invokes like this in Sindarin and I suspect the reason is precisely that this is fire magic and thus involves Gandalf’s carefully hidden Elven ring, Narya the Ring of Fire.

We do, by the by, get told about one other ‘spell’ invocation delivered in a language other than Westron and it is the spell upon the One Ring itself, which Gandalf notes, “For in the day that Sauron first put on the One, Celebrimbor, maker of the Three, was aware of him, and from afar he heard him speak these words, and so his evil purposes were revealed” (FotR, 304, emphasis mine). Gandalf goes on to recite those precise words shortly thereafter: Ash nazg durbatuluk, ash nazg gimbatul, ash nazg thrakatuluk agh burzum-ishi krimpatul, “One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all and in the Darkness bind them.” And invoking the words produces an immediate supernatural result locally (the sky darkens), as if the One Ring responds to them in a way it does not respond to their translation. That suggests to me that the Rings might require invocation in a specific language, the language of their creation, to function properly.

Our two other invocations are delivered in ‘English’ (English for Westron) and take a form I want to note: they are plain language assertions, in the present tense, about the state of the world. Gandalf’s spell to block the Balrog and eventually collapse the bridge is quite simple, “You cannot pass!” (FotR, 392), repeated four times. Of course this comes embedded in a larger speech:

‘You cannot pass,’ he said. The orcs stood still, and a dead silence fell. ‘I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass.’

Note that the orcs, lacking any kind of spiritual power capable of withstanding Gandalf in this moment where he unveils his power, stop immediately, but the Balrog presses forward, leading Gandalf, after a brief clash, to repeat his invocation, ‘You cannot pass!’ one last time. Then Gandalf strikes the bridge with his staff and both his staff and the bridge break, leading the Balrog to tumble down. Which is to say Gandalf told the Balrog something about the true nature of the world – that it could not pass – and and Gandalf was right.

We see the exact same construction mirrored with Saruman. For all of the exchanges of words, Gandalf does not stop Saruman’s effort to use his voice (which I suspect is as much an exercise of craft-magic as any) but only at the end engages in a direct supernatural confrontation:

He raised his hand, and spoke slowly in a clear cold voice. ‘Saruman, your staff is broken.’ There was a crack, and the staff split asunder in Saruman’s hand, and the head of it fell down at Gandalf’s feet. (TT, 222).

Note that Gandalf does not order the staff to break, nor does he say it will break or bids to let it break. He simply declares that it is broken just as he declares that the Balrog cannot pass. These are present tense statements asserting a reality rooted in the Unseen world which then express themselves through the Seen world. Saruman’s staff is broken because he has broken with the will of Eru which was always the true source of his power. We had actually spent several pages seeing that reality as Saruman tries but fails in using his Voice to win over one listener after another that “the power of his voice was waning” (TT, 224). Gandalf, invoking that fundamental reality of the Unseen, spiritual world makes it visible, manifest in the Seen physical world: he declares that the staff is broken and it conforms.

Notably, this moment, where Saruman hurls a fireball and Gandalf blocks it with magic, doesn’t happen. Supernatural beings do not generally fight this way in Tolkien, at least not in fights we witness first hand.

Doubling back for a moment, I think we can also say that our non-Westron invocations actually follow this formula, with a bit of a grammatical quirk. In formal English (which represents Westron), speakers cannot ‘gap’ (that is, drop) the verb ‘to be’ – though in informal English folks do all of the time (think “he a fool” for “he is a fool”) – but in many other languages you can and regularly do ‘gap’ simple present tense forms of the verb to be, especially in poetry. I am not an expert in Tolkien’s linguistics, but this is common enough, for instance, in Latin – especially in poetry – and of course famously throws many Latin students who meet a sentence composed entirely of nouns and adjectives, searching for a verb in vain only to be told to ‘supply est.’59

I think in the same way, we can understand naur an edraith ammen, “fire for saving us” and Ash nazg durbatuluk “One Ring to rule them,” simple descriptions of an object, to be ‘gapping’ a form of the verb ‘to be.’ The temptation would be to supply it in the optative, “let there be” but I think, given the above example, we ought to actually supply it in the present indicative – and indeed, there’s nothing stopping us, which renders the meaning of the invocations as, “[There is] fire for saving us” and “[There is] One Ring to Rule them.” And that is, in practice, the implication of both statements: they are describing something and so by ‘magic’ willing it into existence: fire for saving or a ring for ruling.

In short, then, we have our pattern for ‘magic’ – for exertions of true supernatural power in its most powerful and direct forms: characters exert their spiritual power through plain language assertions about the current state of the world – the spiritual power – works, the world alters itself to accommodate their statement, to make it true or perhaps more correctly, given the present-tense nature of the construction and the profundity of the statements, we might even say to make it always have been true, because what is being made ‘true’ is really a ‘truth’ derived from the more fundamental, more real reality of the Unseen.60 And because the Unseen is more profound and fundamental than the Seen, when its nature is revealed the Seen world, as if snapping to a reality that has already existed immediately conforms.

Gandalf declares “You cannot pass!” and indeed, it cannot. He declares there is fire and instantly there is fire. Sauron announces there is One Ring which will rule and bind the others and there is such a Ring, though note that there indeed has been such a ring for moments at least (for he is only in that moment placing it on his finger), yet it is the invocation that makes that Unseen reality real to Celebrimbor in the Seen world. And of course, Gandalf declares, “Your staff is broken” and, indeed, it is – and in the Unseen sense, perhaps has been for some time.

The Seen world conforms.

As an aside, because it fits nowhere else: it is also clear that these expresses of spiritual power seem generally to require a focusing object to be fully effective. Of course we see this in the staves of the wizards, but equally in Sauron’s spell upon the One Ring and – if my supposition above is correct – Gandalf’s use of Narya to focus his command of fire. Interesting that while both times Gandalf uses the naur an edraith ammen he holds a branch aloft, but only in the first case (FotR 347) does he make use of his staff. I wonder if, unseen to the book’s narrator, he is holding that stick aloft and tossing it (FotR 357) with his ring-bearing hand. In either case, that the object contains a portion of the spiritual power of its individual and its breaking matters is clear in both the unmaking of the ring and the breaking of wizard staves – Gandalf’s at the bridge and Saruman’s at Orthanc – and of course Gandalf’s care to make sure he still had his staff when he went to confront Théoden (TT 137). Of course if we understand Gandalf’s staff may be a part of him as much as the One Ring is a part of Sauron, we may equally understand his reluctance to lay it aside. So while we never get quite as clear a picture on the role of these focusing objects, I think it is a fair supposition that they matter quite a bit.

Tricky Magic in the Golden House

With our formula in mind, I think we can begin to detect moments in which supernatural power is expressed a bit more subtly or perhaps we might say more profoundly, which makes it a bit trickier to assess.

The smallest and first tricky example is Gandalf’s arrival at Meduseld. It seems clear some expression of spiritual power is intended here: “He raised his staff. There was a roll of thunder. The sunlight was blotted out from the eastern windows; the whole hall became suddenly dark as night. The fire faded to sullen embers” (TT, 140). But the nature of the magic is a lot less clear, particularly compared to the very clear and obvious power duel that Peter Jackson substitutes for this moment, complete with Saruman being thrown across a room miles away.

But I think we can make some sense of what is happening now that we have something of a model. For one, Gandalf is doing things with his staff here, raising it at first and then later “he lifted his staff and pointed to a high window” (TT, 140). But there also ought to be words and we are looking not for commands in the imperative mood but rather plain language statements about the state of the Unseen world, realized in the Seen world.

And I think we get two. The first, which produces the roll of thunder, is directed at Gríma, “I have not passed through fire and death to bandy crooked words with a serving-man till the lightning falls” (TT, 140). And I hear you say, “but that’s a past tense statement” but in fact it is, if we can break out a bit more complicated grammar, a perfect tense statement. Tolkien, of course, a philologist whose training included quite a bit of Greek will have known how the Greek perfect tense functions: it expresses a past tense action which has been completed but the results of which continue to the present – a past tense action which creates a present tense reality. What Gandalf is saying is that the fact that he has passed through fire and death – and as we know, emerged as Gandalf the White, sent back with more power and an expanded remit by Eru Ilúvatar – has created a present tense reality that he is not going to be tied up with Gríma.

What to me seals this as the invocation is that ending, “till the lightning falls” because Gandalf then raises his staff and the very next thing that happens is “There was a roll of thunder” (TT, 140) and the light in the windows is blotted out, presumably by the coming storm heralded by the lightning (which will vanish shortly and equally magically). Gríma then moans that they ought to have forbidden Gandalf’s staff (and so he is unable to trap Gandalf in their war of words) and then the lightning falls, “there was a flash as if lightning had cloven the roof. Then all was silent. Wormtongue sprawled on his face” (TT 140). Gandalf thus declares the Unseen reality – that unlike the Gandalf the Grey who had visited this court before, he, having passed through fire and death, is no longer the sort of Gandalf who will be held off by mere words, “till the lightning falls” – and the Seen world conforms to the stated reality: Gríma retreats and the lightning does indeed fall.

The second instance fits our model even more cleanly, though it may just be the conclusion of the same expression of supernatural force:

‘Now Théoden son of Thengel, will you hearken to me?’ said Gandalf. ‘Do you ask for help?’ He lifted his staff and pointed to a high window. There the darkness seemed to clear, and through the opening could be seen, high and fair, a patch of shining sky. ‘Not all is dark. Take courage, Lord of the Mark; for better help you will not find.’ (TT 140, emphasis mine)

Here our sequencing is the complication. Our plain language statement of the Unseen reality is clear enough: “Not all is dark” as is the Seen world conforming to that statement, “There the darkness seemed to clear.” Merely the order is tricky: the Seen world is conforming to the Unseen first, with the statement coming after. But I don’t think this is an insurmountable problem, because remember that the ‘magic user’ is not creating a new reality but merely revealing the Unseen reality, the more fundamental spiritual reality, which already exists.

Also, as an aside, because this fits nowhere else, Gandalf needs Théoden to consent, to “ask for help” (though he does so with actions – leaving his chair and going outside – rather than with words) in order to work his ‘magic.’ This, of course, is what separates Gandalf from Sauron or the fallen Saruman: he has not the will to dominate which is the root of all evil in Tolkien. He will not force Théoden, he will merely show him the better path and bid he take it. Indeed, he will not force Gríma either: even once Gandalf reveals Gríma’s treachery, he urges Théoden to “Give him a horse and let him go at once, wherever he chooses. By his choice you shall judge him,” by which he means if Gríma rides to war with Théoden he might be forgiven, but if – as he does – he flees to Saruman, then he is revealed in his choice.

Underneath the Gate of Minas Tirith

The other major confrontation between supernatural beings that we view directly is the confrontation between Gandalf and the Witch King beneath Minas Tirith’s main gate. This is one of my favorite moments from the book and actually the entire reason I decided to write this nearly 7,000 word post was because I am still sore that Peter Jackson, for all of the quality of his adaptation, got this moment very wrong (in the extended edition). Not only does he have Shadowfax rear up and quail before the Witch King, rather than being, “Shadowfax, who alone among the free horses of the earth endured the terror, unmoving, steadfast as a given image in Rath Dínen” (RotK, 113) but he has Gandalf’s staff shatter, as if Gandalf has lost – or even has nearly lost – this confrontation.

First, I would argue this is a misunderstanding because it can only be overweening, staggering hubris that the Witch King even imagines he has any shot at winning this spiritual confrontation (though overweening arrogance is his great flaw, so it is in character). It’s unclear to me if the Lord of the Nazgûl actually quite realizes what he is up against – he calls Gandalf “Old fool!” and one wonders if he has mistaken Gandalf for an aged lore-master and magic user rather than the far more powerful Maia he is. But there is no doubt in my mind that Gandalf would always be the stronger here. Recall Gandalf’s statement to Gimli at their first re-meeting that, “And so am I, very dangerous: more dangerous than anything you will ever meet, unless you are brought alive before the seat of the Dark Lord” (TT, 122). Note the change from the Gandalf who once demurred that “Against some I have not yet been measured” (FotR 266) – this Gandalf knows himself to be the most dangerous thing Gimli could meet, short of Sauron himself. The Witch King hasn’t a hope of winning this confrontation.

But more to the point, he very clearly doesn’t win this confrontation. Instead, what we get is an expression of supernatural power, same as the others, in the same form:

“You cannot enter here,’ said Gandalf, and the huge shadow halted. ‘Go back to the abyss prepared for you! Go back! Fall into the nothingness that awaits you and your master. Go!’ (RotK 113).

And look what we have: a present tense plain language statement of the state of the world, in particular a clear declaration that it is the case that the Lord of the Nazgûl cannot, is incapable, of entering. The WItch King, of course, dismisses this as words, mocks Gandalf, reveals his iron crown, raises his sword and with dark magic sets it alight (RotK, 113). But you know what he doesn’t do?

He doesn’t enter. Because he cannot.

Once again, I think it is worth stressing that Gandalf does not speak idly: when he is uncertain, he says so. If he thinks something is possible, he says that too, using words like ‘may’ and ‘hope.’ But here he states a cold reality: the Lord of the Nazgûl cannot enter here, the same way that Durin’s Bane cannot pass. A reality about the Unseen world is being expressed. And then, of course, the Seen world conforms to the deeper reality of the Unseen world.

And as if in answer there came from far away another note. Horns, horns, horns. In dark Mindolluin’s sides they dimly echoed. Great horns of the North wildly blowing. Rohan had come at last […] the darkness was breaking too soon, before the date that his Master had set for it: fortune had betrayed him for the moment, and the world had turned against him; victory was slipping from his grasp even as he stretched out his hand to seize it […] King, Ringwraith, Lord of the Nazgûl, he had many weapons. He left the Gate and vanished. (RotK, 113, 125)

In understanding how spiritual power can express itself in Tolkien, I think this confrontation is the essential bridge. Because on the one hand it is, in structure, paradigmatic, complete with that clear, present-tense statement of the state of the Unseen reality. That this is such a confrontation is made clearer in how closely it mirrors Gandalf’s clearly ‘magical’ confrontation with Durin’s Bane on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm: “You cannot enter here” neatly matching “You cannot pass,” and if we missed it, in both cases the villain produces a flaming sword with which to challenge Gandalf (FotR 392; RotK 113). On the bridge, Gandalf and Durin’s Bane are so close in power that both fall and so Gandalf staff breaks as he reaches the utmost of his power, but under the gate, the Witch King is not so near a peer (and Gandalf is now far stronger) and so the Witch King merely withdraws; Gandalf’s staff does not break. But the structure of the supernatural confrontation and its fundamental nature as rooted in spiritual power remains.

What is revealing however in this moment is how that power is expressed. Gandalf does not drive the Witch King from the gate with fireballs or curses or swordplay. Instead, the physical reality of the Seen world conforms to the spiritual reality of the Unseen world: the arrival of the Rohirrim prevents the Witch King from entering and so he “cannot enter.” Again, this mirrors the confrontation on the bridge: Gandalf declares the Balrog cannot pass and indeed he cannot, not because Gandalf is going to punch him out, but because the bridge will break beneath him if he tries. The victory in the spiritual contest is expressed not in direct, flashy confrontation, but in the truth of their vision of the world. Gandalf’s victory in both cases is born out by the fact that his statement about the world was correct, while the Balrog’s unstated assumption and the Witch King’s open mockery were incorrect.

I didn’t grab screenshots, but Rings of Power is equally blunt with ‘Gandalf’s magic, having him summon sand tornadoes, cause trees to bloom instantly and explode and so on.

Of course, Gandalf is not uninvolved with the arrival of the Rohirrim, even if we might not imagine his participation to seem particularly ‘magical.’ Gandalf was very involved! He has – even if he didn’t know it fully – been setting the terms for this very confrontation for weeks now, by pulling Théoden from his depression, aiding him against Saruman, bringing Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas to him (all of whom play crucial roles at Helm’s Deep), all thereby ensuring that when the Witch King tries to enter “under the archway that no enemy ever yet had passed” (RotK 113) it would be the case that he “cannot enter.” The Witch King, arrogant and overconfident, does not recognize this reality in the Unseen world, but Gandalf – the wisest of the Maiar – perceives it, having efforted himself to bring it about. The ‘spell’ is thus the product of Gandalf’s many labors, because as a fundamentally spiritual, angelic being, all of these labors too are expressions of spiritual power, all aimed at producing an Unseen reality, which Gandalf then describes, manifesting it into the Seen world.

You Have Proved Mightest

And now our road, having gone ever ever one turns at last to home and our starting place: Treebeard’s judgement on Gandalf, that he had “proved mightiest,” as if we had seen Gandalf engaged in some direct contest of wills and spiritual power with Sauron, like the confrontations we see between Gandalf and Durin’s Bane, Saruman and the Witch King, and come out the stronger (RotK, 287).

But, my dear reader, we have seen that. We have been reading that for the entire three books.

The remit of the Istari, the wizards, as the Elves understood it is described to us in the Silmarillion, “that they were messengers sent by the Lords of the West [that is, the Valar] to contest the power of Sauron, if he should arise again, and to move Elves and Men and all living things of good will to valiant deeds” (Sil. 299). Only Gandalf stays fully true to this mission (though only Saruman, perhaps, fully failed it) and “Now all these things were achieved for the most part by the counsel and vigilance of Mithrandir [=Gandalf]” (Sil. 304), so it is fair to say that in a sense Gandalf is, throughout the story, directly, personally contesting the will and power of Sauron.

As we’ve seen above, the line in these spiritual contests between ‘magic’ and ‘labors’ is not just blurry but functionally indistinct: Gandalf triumphs over the Witch King in a clear by-the-numbers spiritual contest of wills not by casting lightning bolt, but by having set in motion days and weeks before the movement in the hearts of men which would bring the Rohirrim to Minas Tirith, which is of course, perfectly fitting with his mission. Gandalf may not even have fully known that – in the plan of Eru Ilúvatar – this is what he was doing, setting the stage for that very confrontation. Yet his actions first create a reality in the Unseen, in the hearts of people, which then at the critical moment manifests in the Seen world.

And of course, you can see where I am going with this. Gandalf has been working his ‘spell’ to defeat the evil of Sauron, at this point, for many years kindling in the hearts of Men and Elves the will and courage for valiant deeds most of all in setting Frodo upon his quest and in his counsel priming Frodo to make the crucial choice to spare Gollum (FotR 85-6) and to bring Sam (FotR 90-91), the decisions that in the end, though made by Frodo of his own free will, are the decisions that will cause the Quest to succeed where it might have failed at the very last. As we’ve noted before, while the Seen world of Middle-earth is ruled by physics, its Unseen world is ruled by morality and the choice to do right can ripple through the Unseen world with a profundity that the Seen world lacks. After all, Gandalf himself notes, “My heart tells me that he has some part to play yet, for good or ill, before the end; and when that comes, the pity of Bilbo may rule the fate of many – yours not least” (FotR, 86) and once again, Gandalf’s deep sense of the Unseen reality is fundamentally correct: because Bilbo and Frodo did the right thing and showed pity and mercy (the latter having been encouraged to do so by Gandalf), the Quest succeeds and evil is defeated. Of course that is just one of the many, many interventions Gandalf makes.

All we need is our invocation, our present-tense statement about the state of the Unseen world, as it manifests into the Seen world.

But Gandalf lifted up his arms and called once more in a clear voice.

‘Stand, Men of the West! Stand and wait! This is the hour of doom.’

And even as he spoke the earth rocked beneath their feet […]‘The realm of Sauron is ended!‘ said Gandalf. ‘The Ring-bearer has fulfilled his Quest.’ And as the Captains gazed south to the Land of Mordor, it seemed to them that, black against the pall of cloud, there rose a huge shape of shadow, impenetrable, lightning-crowned, filling all the sky. Enormous it reared above the world, and stretched out towards them a vast threatening hand, terrible but impotent: for even as it leaned over them, a great wind took it, and it was all blown away, and passed; and then a hush fell. (RotK, 252, emphasis mine)

And so we have our complete formula for a confrontation rooted in an expression of spiritual power. Gandalf declares that the “hour of doom” is at hand, and so it is and then that “the realm of Sauron is ended!” a truth that already exists in the Unseen world but which now manifests even as the Captains gaze south into Mordor, the Unseen truth very literally becoming part of the Seen world as they see it. And the spiritual power of Gandalf’s statement, to which the world around him is rapidly conforming, is of course rooted – as was his victory over the Witch King – in Gandalf’s many labors, a ‘spell’ many years in the making.

Treebeard is thus correct when he observes to Gandalf that “You have proved mightiest, and all your labours have gone well” (RotK, 287). It is, of course, in line with a story that already sought to surprise the reader by having the Quest completed not by the Noble Knights (Boromir and Aragorn) but rather by the smallest and weakest creatures, the hobbits, that Gandalf’s great power is revealed not in his physical might or by throwing fireballs or commanding armies, but rather in his wise counsel, in his compassion and his pity: he has overwhelmed Sauron’s power with goodness and in so doing, “proved mightiest.”

In his ability to move others to right action, to one good deed after another whose morality shaped the Unseen world until at last the grand magic of Doing The Right Thing bears out in unmaking the very “realm of Sauron.”

Because it was always the Unseen world, shaped by hearts rather than armies, which mattered the most.61

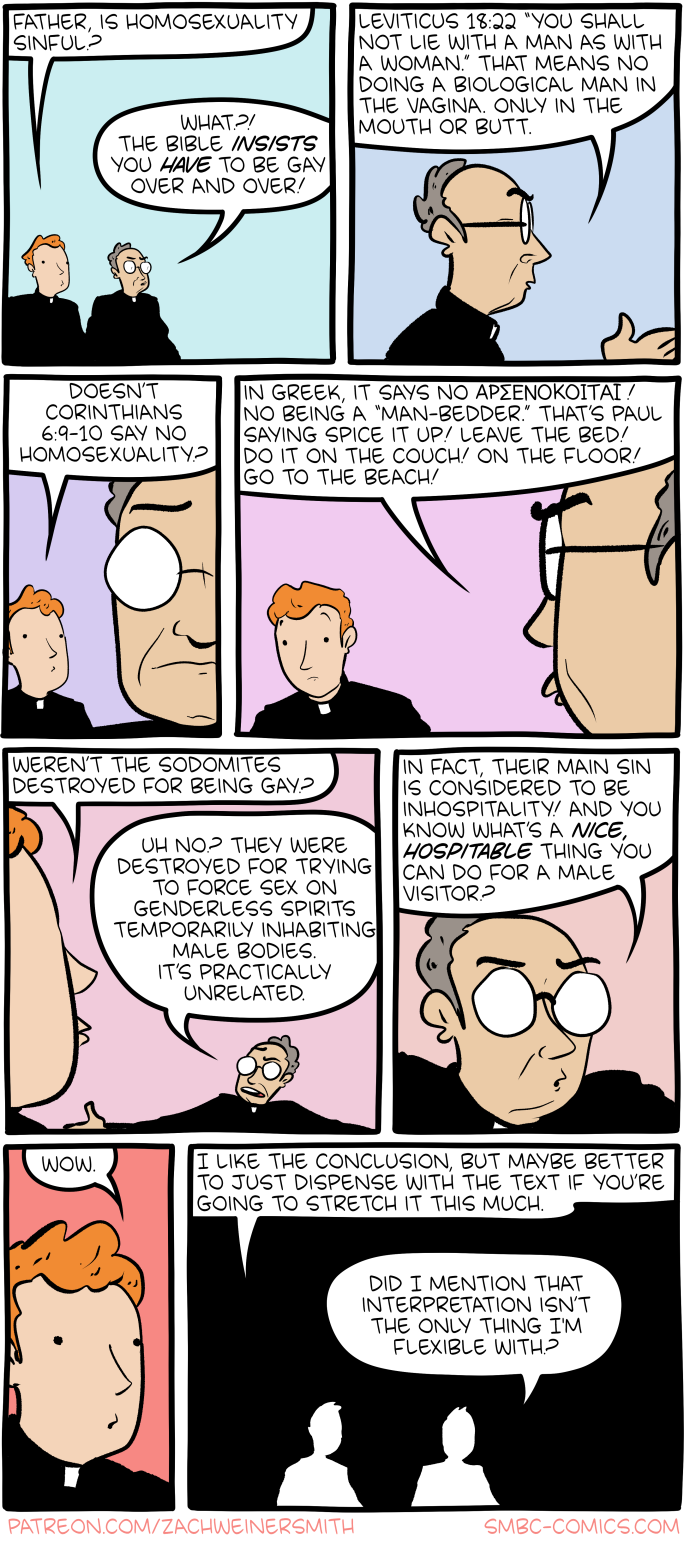

ALT

ALTMy cartoon for this week’s Guardian Books Summer Reading Special.

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

Look, if those exegesis guys get to find whatever they want in the text, so do the rest of us.

Today's News: